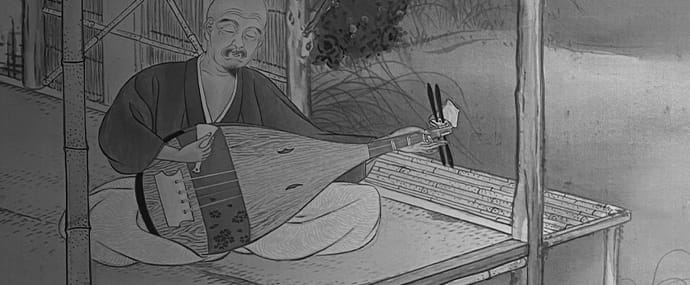

6. Musical Form of a Chikuzen Biwa Ballad

The texture of a ballad is characterized by the interplay of song and instrument: almost every sung line is separated from the next by at least one or more strokes. These strokes often serve to provide the vocal pitch of the next line. After several lines, one of the 180 or so interludes is used to provide a musical illustration of the text just sung.

Almost all vocal elements are pre-fixed linear elements, as are the interludes. The same melodic formulas and a varied selection of the same interludes thus appear in every piece. The artistry now is to adapt these prefabricated elements to the narrative and to give the listener the feeling that every performance is a unique creation. In order to fully exploit the potential of the expressive possibilities of this modular principle, there are several means, which yield variety and color. One factor is the tempo, which can be varied, but then there is also the instrumental attack: playing the same interlude in a soft, aggressive, dreamy, hopeless or joyful style challenges the imagination of the instrumentalist. The limited vocal melodic formulae also provide singers with numerous interpretive possibilities by which they can impart excitement, pathos, or the moving through voice timbre; they can also imitate voices, emphasize the melismatic or the declamatory aspects of the piece in question. In order to engage the listener with the narrative, the performers must be able to draw upon all the expressive techniques allowed by the style.

A ballad usually consists of three parts:

1. makura is a prologue that lasts about four to eight lines. In the middle and low vocal registers, the singer reflects on life or fate in general. Then follows:

2. hon'uta, the main part of the story. It starts usually with one of the highest pitches, ⑥ or ⑦. The most common way of structuring the hon'uta of 100 lines or more is achieved by inserting an arioso (nagashi: see below) or by the poetic caesura of a poem in the Chinese style (kanshi) sung with a specific melody known as shigin. Otherwise, there are no formal constants in the structure of the hon'uta. When the drama of the hon'uta reaches its climax:

3. the ato'uta, the epilogue, which lasts for the final six to eight lines. Here, the performer is expected to pick up the pace and conclude the story with a solemn gravity. The last line is commonly repeated with another melodic formula specific to the doubled lines of the conclusion. With this, the ballad comes to an end.

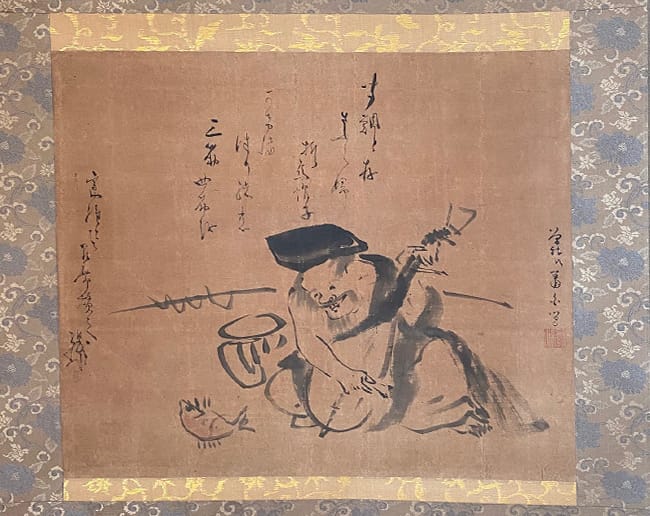

7. The Instrumental Interludes

The music of the chikuzen biwa was initially for a 4-stringed instrument. Even at this point, the instrumental interludes were categorized into “lyrical” and “dramatic”. These two categories covered almost the entire spectrum of expressiveness. Most of the lyrical interludes had bird names: "wild goose", "heron", "sparrow", and more. The dramatic interludes had more pedestrian names such as "unit", or "number": chō no san “unit 3” or jūyonban “number 14”, for example. In the scores, they were indicated on the lower left side at the end of a line.

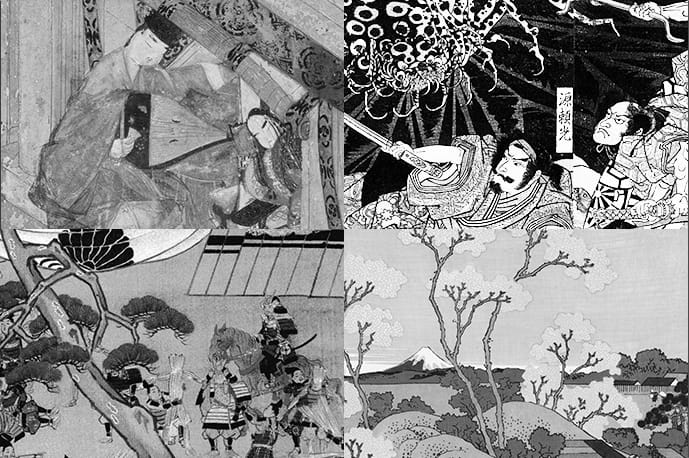

This 4-stringed repertoire was the standard until the mid-Taishō period (1912-1925) when the 5-stringed instrument, which is almost exclusively played today, was created. A few rearranged 4-stringed interludes have been added to the 5-stringed instrumental repertoire, but most interludes were newly composed. Only a few of the bird-named interludes found their way into the 5-stringed repertoire and remain largely unchanged from the original. This creates a multilayered effect. For example, in the ballad Funabenkei, which recounts Yoshitsune's flight, there is a scene on the sea-shore in which his lover Shizuka has to bid him farewell. Before she sings a song in the Chinese style, she dances to the bird-interlude "Phoenix", which is associated with the high culture of Chinese poetry and the elegant life of the capital. “Phoenix” from the 4-stringed repertoire functions here to evoke the past and create a distance from the misery in which all the refugees find themselves.

In the creation of the 5-stringed instrumental repertoire of about 180 pieces, the division of “lyrical and dramatic interludes” was retained. In order to distinguish them from the 4-stringed repertoire, the lyrical interludes were given the names of flowers, bushes and trees. Many traditional flower names were chosen, but exotic species such as “cactus” also appear. (“Cactus” is one of the most beautiful and poignant instrumental miniatures in the entire repertoire.)

Many flowers have associated meanings in Japanese culture. The cherry blossom, or sakura, for example, has an incredibly rich set of associated images. They can symbolize the brilliant but short life of the samurai, these glorious radiant warriors who fell on the battlefield still flush with the beauty of youth, their transient lives resembling the falling cherry blossoms. Given its overwhelming importance in Japanese culture, it is perhaps not surprising that the Sakura interlude is the only one never required in its entirety in a ballad. It is, in my interpretation, too weighty to use as a comment on any textual passage. The interlude can be found in almost every ballad, but always with the indications: "Sakura, opening and ending passage", or "Sakura, opening passage".

The “middle passage” of Sakura is often required, its succinct structure being suitable for the representation of “moving away” or “fleeing”, as seen in lines 46 and 47 in the ballad Kumagai to Atsumori.

-

46. “In the end, the HEIKE were vanquished

47. and retreated to the sea.”If the “middle passage” of Sakura is strongly accentuated, it can be used in combat situations, as in Miyako ochi lines 26./27.

-

26. "And pushed forward with his troops like ocean waves.

27. Arrived on the pass of Osaka, the riders formed.”Other flowers such as “plum blossom”, “camellia”, “daffodil” etc. also have cultural connotations. They are discussed in the music commentaries of the ballads, where they appear.

The dramatic interludes are called seme, "attack", by the players. In these virtuoso and often tumultuous instrumental pieces with numerous strokes in which all the strings are played, the percussive character of the biwa, which the Japanese call a "string percussion instrument", dagengakki, becomes evident. In the seme, too, there are varying possibilities in that sometimes only parts of an interlude are required, which when listening to a biwa performance can impart the impression of it being a new interlude. This impression is readily understandable as many interludes are very similar or partially identical. This contrast created by the fusion of the new yet familiar has its own charm for the listener.

8-1. Sound System and Concept of Pitches

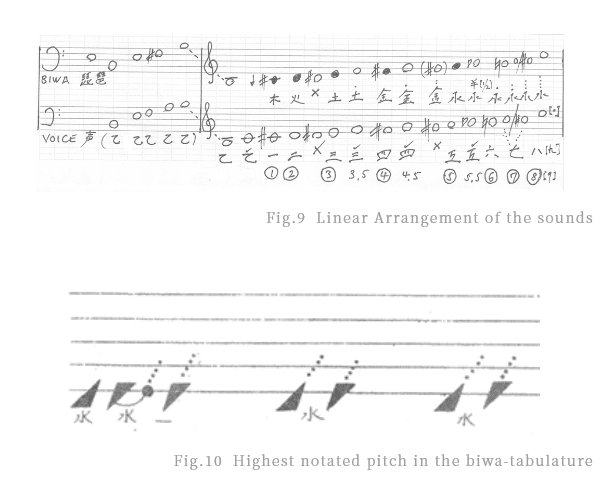

The scale used in chikuzen biwa could be called chromatic. The tonic here is provisionally set to e'. The only pitch that does not exist in scale is d#', which would be the leading tone according to Western music theory. The tone g#' exists, but so seldom appears that it is also almost nonexistent. The vocal range spans two and a half octaves: from the fundamental B, which is the pitch of string II to an e'' two octaves and a fourth above. In the instrumental notation, the highest pitch e'' is realized with the symbol of the 5th fret, 水, with 4 dots above it.

Chikuzen biwa is a narrative and the lyrics are thus of paramount importance for the singer. A richly crafted sung melody line is only appreciated if it does not detract from the narrative content. Correct diction and delivery are far more important than a precise pitch.

As mentioned above, the first pitch the performer sings is indicated by a numeral at the head of the text-line. Any changes of pitch afterwards are denoted by neume-like indications (fushi indications) in the form of curled lines or commas. The numbers for the vocal pitches range from ① to, ⑧. One higher note than ⑧, (f''), is only indicated by fushi indications.

| ① | ② | ③ | ④ | ⑤ | ⑥ | ⑦ | ⑧ | (⑨) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c#', | d', | e', | f#', | a', | b', | c" / c#", | e" | (f") |

The pitch b, a major second below ① is notated with the character otsu 乙, which normally means “deep”. This is in contrast to kō 甲 “high”, which is a term first found in Buddhist chant shōmyō and in heike biwa, but no longer used in chikuzen biwa. The vocal register includes at least four more pitches below the b of otsu (a, f/f#, e and B). There are no symbols for these pitches, and the teacher instructs the student to sing “one pitch lower” or “even lower” and demonstrates the required pitch. In the notation, fushi indications once again provide the directives for this lowest vocal register.

The upper register is ambiguous. The number ⑦ can indicate either c'' or c#'', but the choice is often left to the singers and their inspiration. The pitch ⑧, the tonic, is often used, but seldom indicated with a number. The note above, f'', is not understood as an independent pitch, but it is only briefly produced by capable singers when they wish to emphasize the tonic ⑧ by creating what could be called an upper leading tone.

The limited terminology of the vocal notation highlights the importance of textual delivery over pitch in this genre.

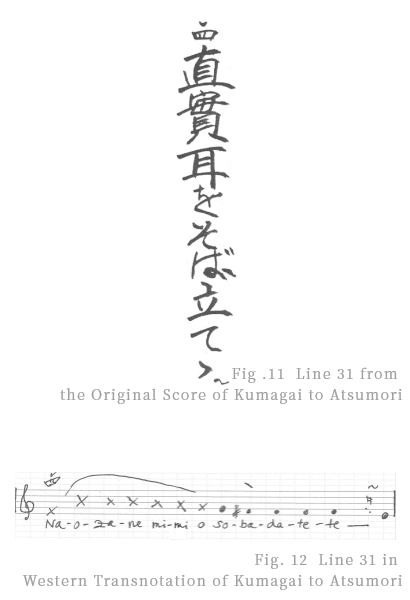

One unique aspect of the chikuzen biwa vocal style must be introduced here (refer to Fig.10./11.): the graphic representation of the pitch g'. There are rare instances in which this pitch is immediately sung when indicated. The pitch g' is written with 四 , or “④chon”. For the performers, chon, usually signifies that the note is to be a minor second higher, and is rendered with a small check over the number. When this check, chon, is over ④, it signifies a departure from the scale by a section of free declamation performed in a large melodic arc. The return to the tone system, usually after 7 syllables, is indicated with a comma-like fushi-indication on the fourth to last syllable, and means that the fifth to last syllable, which is the beginning of a five-syllable poetic text-line, is to be sung on f#'.

The music sample (Fig.10./11.) is taken from Kumagai to Atsumori, line 31.:

31. 直實耳をそば立て “When Naozane listens to these sounds”

The name “Naozane” is sung here in a free declamatory arc, fitting well the warrior's heroic appearance.

8-2. The Arioso Form Nagashi

In the chikuzen biwa narrative genre, one melodic model spans three lines of text. The pronounced melismatic quality of this model is such that it will be referred to as 'arioso' in this publication.The notable aspect of this melodic model is not merely an abundance of vocal flourishes, but that it is a passage in which the instrument accompanies the singer.

There are several nagashi. The most important are the four seasons. Other nagashi include asahi, naniwa, tsuyu, and more. The primary difference is the melody of the 1st line, sometimes also in the 2nd, but seldom, if ever in the 3rd line. The spring nagashi is naturally more jubilant than the summer nagashi; the autumn nagashi is slightly melancholic, whereas the winter nagashi is distinctly sad. The use of a seasonal nagashi for any given text is not dependent on a seasonal reference in the text. For example, the ballad Rashōmon mentions sakura, and the time frame is thus clearly spring, but given that it has started to rain, the composer has chosen the autumn nagashi. See lines 25-27: Autumn nagashi

-

24. The haze spins into threads of rain

25. that softly dapple the water of the pond,

26. weaving patterns of figured cloth on its surface.

27. Cherry blossoms scatter on the shoreThe decisive factor for the composer in choosing a nagashi is always the mood or deeper meaning of the text rather than a superficial linguistic connection with the lyrics. Another creative approach by the composer can also be seen in his flexible handling of the nagashi. The same principle of partial use, as seen in the interludes, is also seen with nagashi. Sometimes, a single line of text can be sung with the 1st or the 3rd line of the nagashi melody. There are also instances in which a line of standard recitation is inserted after the 1st melodic line of the nagashi, after which the performer then returns to complete the 2nd and 3rd nagashi lines. Occasionally, minor melodic variations can be made to the original melody. All in all, this allows for a rich palette of arioso passages of varying lengths that emerges from the narrative flow.

8-3. Singing Chinese Style Poems with Shigin

The performance of nagashi has always been an important criteria in the judgement of a singer's abilities. The singer can display also his prowess in shigin, the singing of Chinese poems (kanshi) with a predetermined melody that became very fashionable in the traditional art world after World War II. Shigin-schools mushroomed with thousands of members. Shigin in chikuzen biwa follows the standard melodic flow of shigin common to all schools, but nonetheless has some elements which make it distinctive. Given that chikuzen biwa is a narrative genre, the tendency is to express the meaning of the poem much more explicitly than in most shigin schools in which the beauty of the voice and the skillful execution of micro-melodies are the main focus. The specifics of this narrative approach to shigin in the Tachibanakai style cannot readily be found in the notation, but can be heard in the singing. The biwa performer's concern focuses on meaningful voice-coloring and clear emphasis on crucial words rather than vocal prowess.

In conversations with YAMAZAKI Kyokusui, she mentioned that she created a new genre of biwa music in the late 1960s as a response to the increasing popularity of shigin, and called it bigin, a term composed of biwa and shigin.

These ballad-songs are short, have a limited number of simple interludes, and are replete with shigin and nagashi. They are meant to be technically easier to master than the biwa ballads, and thus attracted new biwa students from the large crowd of shigin amateurs. Structurally, the piece Dannoura hikyoku comes very close to the newly created bigin: however, as bigin is an independent genre, this work is not pure bigin. Bigin also has an independent school-organization, the Yamatoryū, directed by YAMAZAKI Kyokusui's granddaughter, YAMAZAKI Kōjō.

References

岸辺成雄他編(1981~1983)『音楽大事典』1~6巻、平凡社

平野健次、上参郷祐康、蒲生郷昭監修(1989)『日本音楽大事典』平凡社

国立劇場編、小島美子監修(2008)『日本の伝統芸能講座 音楽』淡交社

武蔵野音楽大学楽器博物館編(2003、2011改訂)「武蔵野音楽大学楽器博物館研究報告書 Ⅸ」