Prologue

There are several reasons behind the motivation for this project. One significant reason is the dearth of research on the culture of the biwa, even in Japanese. Neither is there a comprehensive monograph on the biwa, an instrument that has enriched Japanese musical culture in various forms and styles for over a thousand years.

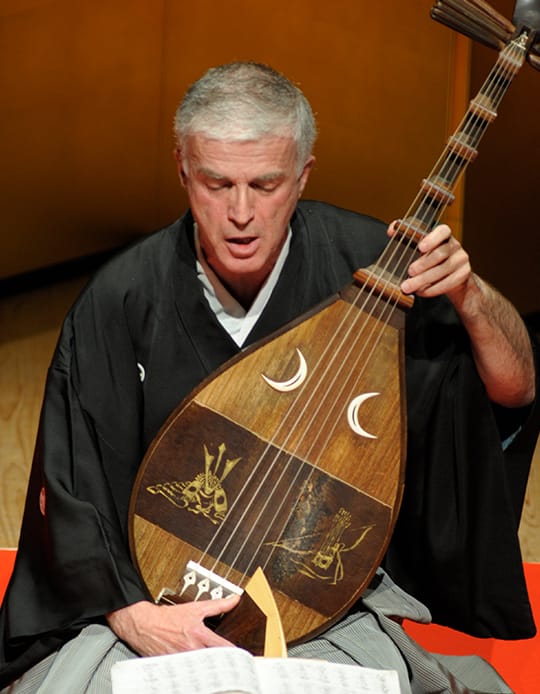

The present study of 22 ballads cannot, of course, completely fill this lacuna; neither does it claim in any way comprehensiveness. Practical considerations led to a narrow focus. In 1983, I came to Japan as a musicologist to immerse myself in the culture of biwa - specifically chikuzen biwa, which has yielded two “Living National Treasures” since then - and soon realized that the absence of music research in this field made it impossible to form a coherent picture. I was soon convinced that the most sensible approach would be to start at the beginning, to engage with this music directly in a practical fashion, and become a chikuzen biwa player. It seemed to me that history, practice and reception of this art could only be understood through concentrating on the biwa texts, on the singing, on the instrument, on the communication between master and student, and on the performance practice in contemporary Japanese society. With this, an insider's view of this lute-ballad culture would be possible, this view then serving as a basis for in depth studies of Japanese music history.

First and foremost in my practical studies was the comprehension of the ballad texts. The lack of a precise understanding of what I was singing or reciting would render any pursuit of this art pointless. The biwa texts are linguistically far removed from the modern Japanese language, and even difficult for the Japanese of today. My intensive study of the ballad texts began immediately with my first biwa lessons, the result of which is the core of this publication.

With the development of musical proficiency, I began performing in Japan and abroad. It then became clear that translating the texts was not only a necessity for me as a biwa performer, but also for spreading this art outside of Japan. For a non-Japanese audience, an appreciation of this musically unfamiliar art of story-telling is greatly facilitated with a solid translation.

This study may therefore serve as a tool for the international promotion and understanding of an important Japanese music genre. Furthermore, a linguistic, historical, and music-analytical introduction to the 22 pieces is unquestionably useful for biwa students from the Tachibana Association (Tachibanakai) in Japan. A Japanese teacher only teaches the practical aspects of biwa performance, and rarely explains the background of the music or the texts. Ms. TACHIBANA Kyokutei, the current director of the Tachibana Association and daughter of the headmaster, welcomed the possibilities this study has to offer.

The entire repertoire of the Tachibanakai comprises 84 pieces, only a quarter of which is presented here. The selection of pieces is based upon two criteria, the first of which constitutes a concentration on those pieces that I had studied and performed on stage over the last 38 years. The second criterion is based upon the extent to which a ballad belongs to the present-day repertoire. Some of the 84 pieces, for example, are now very seldom played. At the same time, however, not all the commonly studied and performed pieces are included in this study. It seemed important to include the widest possible range of content and style. The story of the first ballad, Adachigahara, can be dated to the 10th century, while the last, Saigō Takamori is a heroic story from the late 19th century. In my selection, at least one ballad is related to one of the major eras between the 10th and the 19th century.

Chikuzen biwa was not created only as an entertainment but was also considered to be educational. It was intended to reinforce an awareness of Japanese history and its greatness in the early 20th-century populace, a time when everything from the West was fanatically admired while traditional Japanese values were dismissed. In my selection, the historical aspect of a ballad content was important, but stylistic considerations were equally valuable. In terms of compositional style, all ballads adhere to the same structure — a fixed combination of instrumental interludes and vocal melodic formulas that is the trademark of the genre. There are, nevertheless, distinctly “song pieces,” such as Miyako ochi, but also more “narrative pieces,” Ataka, for example. All of these works were created by the founding head of the association, TACHIBANA Kyokusō I. Only a few ballads were composed by my teacher, YAMAZAKI Kyokusui. Her pieces have a distinct personality: YAMAZAKI, a “Living National Treasure,” was blessed with formidable instrumental technique and even invented new techniques. Her works accordingly emphasize the virtuoso side of the instrument. The vocal parts also include elements that differ stylistically from the pieces of her teacher and mentor, TACHIBANA Kyokusō I.

Regrettably, many beautiful and important ballads could not be included in this selection of 22 pieces. I have also chosen two versions of the same story, Dannoura and Dannoura hikyoku, as they clearly illustrate the difference between narrative” and “song”. I also believe this selection to be important as YAMAZAKI Kyokusui's lyric interpretation of this tale, Dannoura hikyoku, reveals the contemporary Japanese understanding of this most important historical event: the battle which brought the elegant courtly epoch of the Heian period (794-1185) to an end.

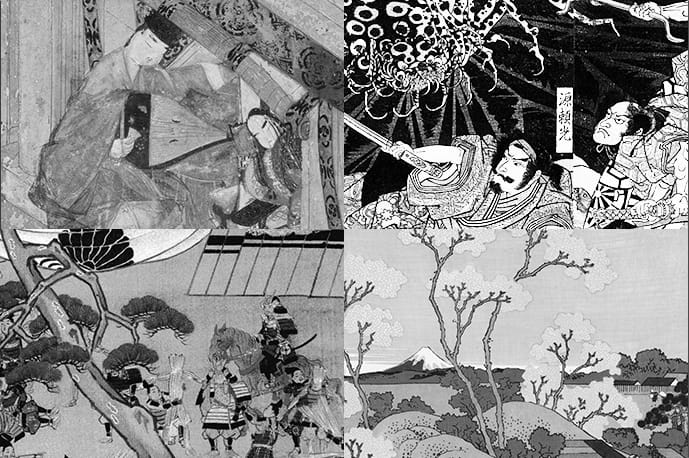

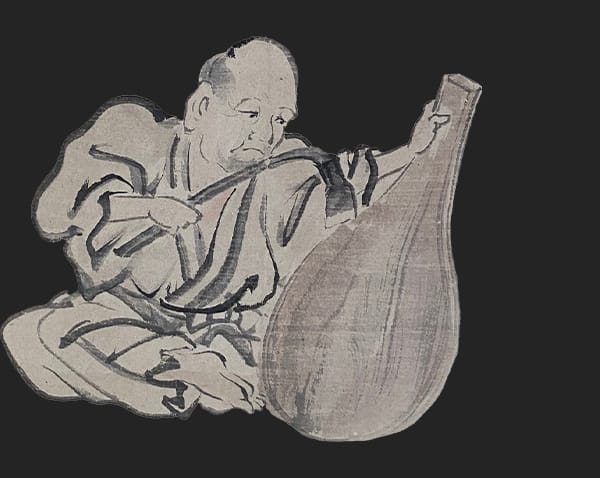

A large group of pieces in this collection constitutes works popular for both performers and audience, and consists of tales about the war between the HEIKE and the GENJI, many of which are based on the Heike monogatari. This epic was performed for centuries to the accompaniment of the heike biwa, which, in terms of playing and style, is as different from the chikuzen biwa as the harpsichord is from the modern piano. But it is not only the religious and philosophical background of this epic, but perhaps more the romance of the Tale of the Heike that has influenced all later biwa cultures. In the present consciousness of the Japanese, the recitation of stories from Heike epics is still the epitome of “the Art of Biwa”.

Profile Silvain Kyokusai GUIGNARD

Born in 1951 in Aarau (Switzerland). Piano studies at the Zurich Conservatory with Hans ANDREAE. 1975 piano teaching diploma. Studied musicology (Prof. Kurt von FISCHER), Japanese studies and ethnomusicology at the University of Zurich. 1983 PhD with a study on CHOPIN's Waltzes. Scholarship from the Japanese Ministry of Education (Monbushō) for biwa studies. Entry into the Postgraduate Course at Osaka University. Beginning of the practical biwa studies with Ms. YAMAZAKI Kyokusui. 1988-99 teaching position at Osaka Gakuin University. 1991 guest lecture at Duke University in North Carolina. Concert-lectures at the Metropolitan Museum in New York, at the Cleveland Museum of Art and at the University of Fine Arts in Los Angeles. 1993 Cultural Encouragement Award of the City of Takatsuki. Beginning of the series “Biwa Plus” (1994-2013, production of 20 concerts), followed by the series “Biwa no shirabe ni…” (2015-2019, production of 10 recitals), sponsored by Ms. TAKAKUSA Wako (Bright One Co., Ltd). 1996 master title shihan for biwa recitation and special prize at the 33rd biwa competition of the Japanese Biwa Society in Tokyo.

1999-2003 Professor of Musicology at the Women's College, Dōshisha University Kyoto. 2004-2021 Professor of Musicology at the International Department of Osaka Gakuin University. Teaching assignments for Japanese art and cultural history. Numerous concerts - partly with the support of the Japan Foundation - in Germany, Switzerland, Australia and America. From 2006 biwa studies with Ms. OKUMURA Kyokusui. Member of the Okumura Kyokusuikai since 2013. 2014 title shūshihan (“Excellent Master”). 2015 Otsu City Culture Prize. Numerous publications in German, English and Japanese on the culture of biwa music and CHOPIN.

Acknowledgements

-

MAYEDA Akio and YAMAGUTI Osamu

My greatest thanks go first of all to the mentor of my studies in Zurich, Prof. em. MAYEDA Akio. I studied Japanese music for several years in his lectures and seminars, and he advised me to choose the biwa lute culture as a research topic. He paved the way for me - after my doctorate on CHOPIN's Waltzes - to go to Japan on a scholarship and to study under the professional guidance of Prof. em. YAMAGUTI Osamu at Osaka University. I am most indebted to Prof. YAMAGUTI who introduced me to Ms. YAMAZAKI Kyokusui, with whom I studied chikuzen biwa for 23 years.

-

YAMAZAKI Kyokusui

Ms. YAMAZAKI, the first biwa performer to be honored in 1996 with the title “Living National Treasure”, was already 77 years old when I was introduced to her as a biwa student. I was the first foreigner she had taught, and since she didn't speak English and had no education in Western music (she could not read Western staff notation), she was unsure if she could teach me. Teaching me the biwa was for her the same adventure as it was for me learning to play and sing biwa music. I am deeply grateful to her that she soon fully accepted me and never gave the impression she thought that I, as a foreigner, would never understand this art. She consistently treated me as a Japanese student, which also meant that she followed the traditional Japanese art concept of learning-time in my education. An "intensive course" of one or two years was never considered. She taught me that it takes a long time to learn an art in its depth and that a music student will grow with the art he is learning. This whole process requires an immense patience, a patience she had with me for 23 years until she died shortly after her 100th birthday. Without the strong artistic leadership of this woman, my research project would have come to a close after only a few years.

-

OKUMURA Kyokusui

Ms. OKUMURA Kyokusui is Ms. YAMAZAKI's most outstanding student, and after her death in 2006, took over YAMAZAKI's students. I was thus able to continue my studies under Ms. OKUMURA and consolidate my repertoire in the first years of my work with her. She has always been an adamant teacher; but this is the best thing that can happen to a student. I have also studied new pieces with Ms. OKUMURA and always admired her indomitable adherence to the purity of the Tachibanakai style. Ms. OKUMURA also became a “Living National Treasure” in 2015, which only highlights her abilities with the art of the chikuzen biwa.

-

TACHIBANA Kyokutei

Ms. TACHIBANA Kyokutei, the future chairman of the Chikuzen Biwa Japan Tachibanakai (jiki iemoto), carefully checked the facts in the English and Japanese versions of the introductory manuscripts. She contributed invaluable information on the history of chikuzen biwa and notably on the history of the TACHIBANA family.

-

KOMODA Haruko

Ms. KOMODA Haruko, professor at Musashino Academia Musicae, helped in her admirable academic way to shape the introductory manuscripts. I am most grateful for her advice and criticism as the most eminent specialist on biwa history in Japan. She kindly informed me about the latest developments in the field of biwa research in Japan in a swift and concise manner.

-

KANDA Yasuko

When I came to Osaka on my scholarship from the Ministry of Culture in 1983, prof. em. KANDA Yasuko was initially my private Japanese teacher. Years later, luck would have it that Ms. KANDA became an assistant professor of Japanese Language Studies at Osaka Gakuin University, where I also taught. Ms. KANDA is a great music lover, but also an outstanding violinist. She helped me with my biwa concert-productions from the beginning and a few years later, she suggested that I thoroughly study the texts of the biwa ballads. Later, her introduction to my colleague, prof. NOGUCHI eventually provided me with the encouragement to start planning this book: it goes without saying that she became a member of our team. With her background as a musician, she then suggested that all ballads be commented with music-notes. Ms. KANDA, also fluent in English, carefully examined the English translations and manuscripts and translated the English texts into Japanese. I am deeply grateful for her unwavering support of this project since its beginning.

-

NOGUCHI Takashi

Prof. NOGUCHI Takashi was the central person in the team when it came to a deeper understanding of the ballad texts. A specialist in classical Japanese, he has a profound and extensive knowledge of Japanese history. Mr. NOGUCHI made every effort to clarify all details, and had our complete admiration for his unerring scientific approach to editing problems. Through him, I gained unexpected insights into the background of the ballads and had the confidence that his handling of the Japanese texts reflects the most modern standard of philology.

-

Philip FLAVIN

Prof. Dr. Philip FLAVIN was responsible for the English revision of all texts in this study. Since he speaks and reads excellent Japanese himself, there were never any communication problems when translating. His background as a practicing musician was also of great help. He is a professional shamisen player and was also a biwa student of Ms. YAMAZAKI for a short time. Mr. FLAVIN is a musicologist, but he also has a considerable knowledge of Japanese literature and art. He used his exquisite sense of English style for this linguistically demanding project, for which I am deeply grateful.

-

Roger WALCH

The filmmaker Mr. Roger WALCH was responsible for the sound recordings of the ballads. Since he is a jazz pianist himself and has already made many professional recordings in his career, I am grateful to him for accepting the modest setting for the recordings. All 22 ballads were recorded in our living room in Otsu for over five years. Although this location can never compete with a music-studio, Mr. Walch was able to achieve a recording quality that goes far beyond an amateur level with the choice of excellent microphones and a clever setting in general. Since Mr. WALCH is fluent in Japanese, there were hardly any problems when cutting the takes. It is thanks to his sensitivity for the sound-conditions that the recordings show the best I was able to achieve as a biwa-singer and instrumentalist.

-

Annemarie GUIGNARD

Without the understanding and help of my wife, nothing could have been accomplished.

Greetings

Chikuzen Biwa Tachibana School Japan

Tachibana Association

Vice Chairman / Next Head of the Association

Hōmeiin TACHIBANA Kyokutei

-

To the Publication of the Chikuzen Biwa Study by

GUIGNARD Kyokusai and his TeamI first heard about Mr. GUIGNARD Kyokusai when YAMAZAKI Kyokusui, the artistic leader (sōhan) of the Japan Tachibana Association, told me that she had started teaching biwa in Japanese to a student from Switzerland. Given the small number of biwa-players in Japan, I was delighted to hear that somebody from overseas was interested in the traditional Japanese art of biwa, but in all truthfulness, I assumed his interest was primarily academic and thus held no expectations that he would continue. Since then, however, I have had many opportunities to listen to his performances in biwa-meetings and concerts, and was delighted to see his biwa skills gradually improve as well as his Japanese.

Today, Dr. GUIGNARD is the only fully accredited non-Japanese chikuzen biwa performer in the Tachibanakai. His professional title, Kyokusai 旭西, is comprised of the two characters, 旭 kyoku, which means 'morning sun or rising sun', and 西 sai (or 'west'). TACHIBANA Kyokusō II, the Tachibanakai iemoto, created this name specifically for him as the second character is used in the Japanese realisation of Switzerland, Suisu 瑞西, if nonetheless read as su rather than sai. Kyokusō II also created his Buddhist name, Hōzui'in 法瑞院 - referring with the character瑞 zui to sui of Suisu.

“CHIKUZEN BIWA Japanese Narrative to the Accompaniment of the Lute biwa is the first comprehensive overview of chikuzen biwa. What few books and articles there are all contain misinterpretations and statements not based on facts. TACHIBANA Kyokusō II, the present iemoto of the Tachibanakai, and I therefore deeply appreciate the time-consuming research by Prof. Guignard and his team with this publication of the first accurate history and theory of chikuzen biwa.

For those of us whose first language is Japanese, we seldom think about meanings, definitions, and concepts of the words we use in our daily lives. As with English, Japanese has many ambigous and polysemous words. Prof. GUIGNARD's analysis of biwa texts relies upon a sensuous interpretation, which he realizes in his imaginative and creative performances.

In the early years of chikuzen biwa - the time of my great-grandfather, TACHIBANA Kyokuō I, the founder of the Tachibanakai - written collections of the instrumental interludes (danpōbon) did not exist and the transmission of the interludes and the vocal settings was purely oral. When my grandfather, TACHIBANA Kyokusō I, was 19 years old, he devised and created the first fixed forms for biwa music and suggested their publication to his father. Finally, with the approval of the founder, the instrumental score, “Reviewed by Tachibana Kyokuō, Collections of the Instrumental Interludes of Chikuzen Biwa, Tachibana Kyokusō Edition”, was published. This publication of the instrumental interludes greatly faciliated the studying and teaching of this art.

Since the founding of the Japan Tachibanakai, TACHIBANA Kyokusō composed over 400 works. He organised these works into thematically cohesive 'music books', and carefully noted all aspects of the performance, vocal and instrumental, for each piece. Today, the pitch, the micromelodies at the line endings, and instrumental interludes are absolutely clear. These carefully notated musical settings allow the performer to develop a clear idea of the composer's intention and thus develop his own intepretation of the piece.

The scores enable the performer to create an expressive rendtion of a piece that touches the listener by conveying the emotions of the ballad's characters and the scene. Biwa is a narrative genre, or katarimono ('the telling of stories'), but rather than merely singing or delivering texts, biwa narrative is expressed with a depth and dimensionality that arises from the interludes' function as commentary on the sung text, the choice of vocal pitches, phrasing (maai), and timbre that emphasize meaning. Expressive Japanese biwa-narration is only achieved through the synthesis of singing, playing, and a profound understanding of the text.

In this survey, Prof. GUIGNARD has approached chikuzen biwa from various perspectives garnered through his many years of studying the art. His training as an academic, and the unique insights available to the non-native Japanese has allowed him to develop a valuable third-party viewpoint.

I believe that this book - created with the help of a superb research team - is the culmination of Prof. GUIGNARDS's 38 years of research and musical engagement with the biwa. I also envision this will contribute immensely to the growth of interest and research in the narrative arts of Japan. For those who hear the biwa for the first time, this text will unquestionably promote a deeper understanding of the biwa and its tales. It will also challenge those who have pursued this art to reconsider and reflect upon it once again. -

Hōwain OKUMURA Kyokusui

The Chikuzen Biwa Japan Tachibana School

Tachibana Association

Executive Director / Grand Master of the Association

“Living National Treasure”We biwa performers are very sensitive to "pitch", "rhythm", "timbre", and more, but because Japanese is our native language, we commonly overlook details without being aware that we have done so. GUIGNARD's publication, however, has provided us with a unique opportunity to think anew about the ballads. Despite GUIGNARD not having been raised and educated in Japan, his research will nonetheless be an invaluable resource for Japanese performers as well.

-

SUDA Seishū

Chairman of the Japanese Biwa-Society

Mr. GUIGNARD came to Japan in 1983 and focused on chikuzen biwa, studying under the outstanding musician, YAMAZAKI Kyokusui. Today, he is a representative chikuzen biwa player whose art is admired by everyone.

In this project GUIGNARD, introduces 22 ballads from the Tachibana Association with detailed information for both text and music, and has also made his performances of the ballads accessible in this website. His performances will raise images and echoes of the divine mastery of the late Ms. YAMAZAKI.

Guignard has also translated all the texts into English and German, and the art of chikuzen biwa will now be disseminated throughout the world, a truly remarkable accomplishment. His research is of immense importance for biwa music in Japan and for the appreciation of Japanese culture in general. I admire this achievement from the bottom of my heart.

On June 2nd 2017, I heard him performing the ballad Nasu no Yoichi in the Hatoyama Hall in Tokyo (Bunkyo Ward Otowa) and was very impressed. There was a brief explanation to the audience of about 100 people who had gathered in the large hall on the 2nd floor just as the light of the setting sun was shining during his performance of an interlude called “Paulownia”. GUIGNARD demonstrated how the slow regular rhythm of this instrumental pattern was intended to let the listeners imagine the pace of a horse.

“He sat on a black horse, a brawny and stout steed, in a golden studded saddle and rode his way. He took a fresh grip on his bow, pulled the reins and proceeded towards the sea.”

The performance reached the climax, and the atmosphere of the venue evoked the scenery of the beach of Yashima, stained by the setting sun.

“For a time, (the fan) floated, tossed and buffeted in the spring wind, afterwards made an abrupt descent towards the sea. In the rays of the setting sun the red fan floated on the white waves bobbing up and down. Out on the sea the HEIKE beat their gunwales with joy, and the GENJI on the land struck their quivers.

After a brief silence, the entire audience applauded with an ovation in recognition of his performance. Nasu no Yoichi is also included in the recording collection of the website and we look forward to receiving praise from all over the world. -

Professor Haruko KOMODA

Musashino Academia Musicae

I am extremely pleased that Mr. GUIGNARD has completed his publication on the biwa. This instrument was introduced to Japan before the Nara-Period (710-794), and its roots can be traced to West Asia. It is thus an instrument with remarkable historical and geographical expanse. The chikuzen biwa, which Mr. GUIGNARD pursues in this study, enjoyed a nationwide popularity in Japan from the late 19th century to the early 20th century, with satsuma biwa. During this period, Western music was introduced into Japan, and children learned Western-style songs at school. Famous Japanese composers, such as TAKI Rentarō and YAMADA Kōsaku, wrote full-scale pieces of Western music. In this era, however, it was the satsuma biwa and the chikuzen biwa that opened new worlds of traditional Japanese music without being influenced by Western music.

Within Japanese music history, the history of chikuzen biwa music is extremely short, and its evaluation as "traditional music" remains unformed. Only recently, have a few Japanese music historians started research in this field. Those who found the biwa worthy of academic pursuit were primarily non-Japanese, such as GUIGNARD, who discovered a distinctly Japanese essence in this music. He settled in Japan, learned chikuzen biwa, and while pursuing a career as a performer nonetheless has accumulated research achievements throughout his life.

The Meiji government's efforts in implementing Western music into public education resulted in Western music now being familiar to many Japanese people, while traditional Japanese music has become an 'ethnic' music for them. Under such circumstances, I think that this publication - unquestionably his life work - will allow the Japanese to once again review and rediscover the appeal of traditional Japanese music. The English and German translations will facilitate the introduction and dissemination of this music abroad.

I have many memories of Mr. GUIGNARD - listening to his performances, working with him at a study group, helping with writing a treatise, and asking for help on a performance trip to Europe. I have always been impressed by his earnest efforts. I would like to express my heartful gratitude to Mr. GUIGNARD and hope that this study in chikuzen biwa will be widely read and serve a seminal role in future research.