Kyoto-search

hirano kuniomi

平野国臣

Introduction

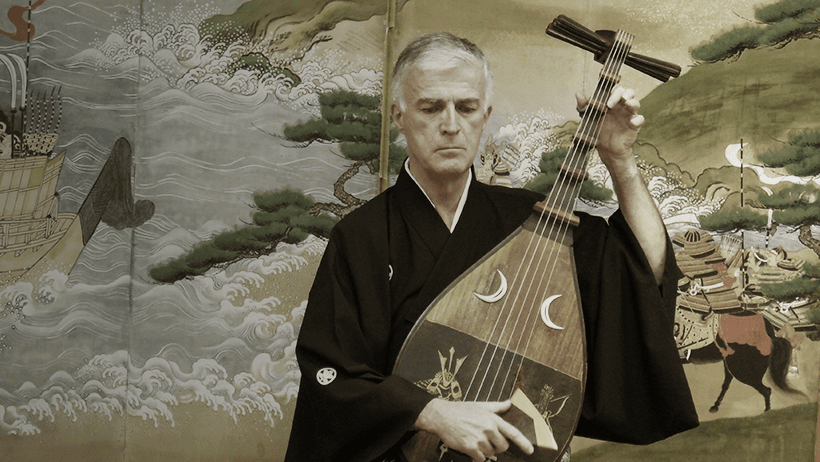

HIRANO Kuniomi was born 1828 in Fukuoka, a region formerly part of Chikuzen, a province located in Kyushu that existed until the Meiji-period government restructured the country. Chikuzen is also where the chikuzen biwa originated, which explains the intent to poeticize the last hours of this local hero in a ballad.

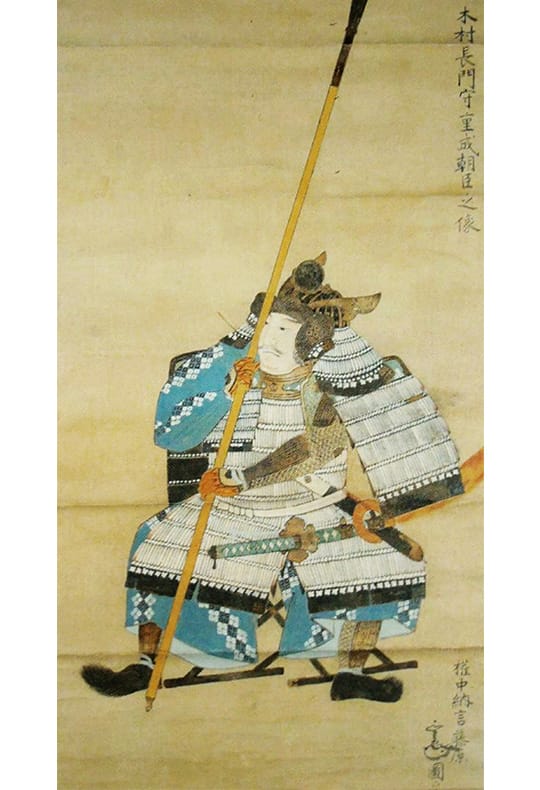

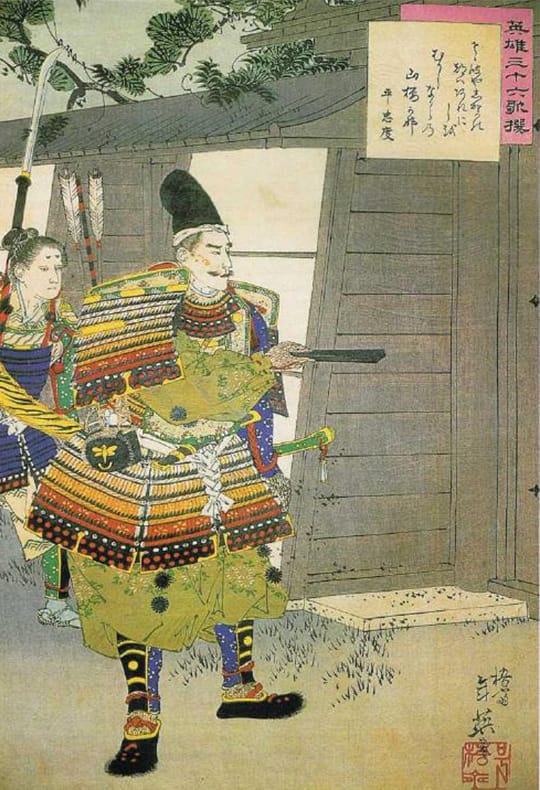

Kuniomi belonged to the party favoring the rule of the Emperor over the rule of the shogunate. He was in close contact with the famous samurai who supported the restoration, the culmination being the return of government rule to the Emperor Meiji. In his youth, he acquired a profound knowledge of Japanese History (kokugaku), and influenced by his studies, became a conservative admirer of imperial rule. With Commodore Perry’s arrival in Uraga (Yokosuka) in 1853, he moved to Edo where he trained in kendō (traditional Japanese swordsmanship). Even today, he remains a highly venerated figure in kendo circles (jōdō). His training in the martial arts only reinforced his conservative political beliefs, and he began to restrict his wardrobe to extremely antiquated garments, such as kariginu, the “hunting robe” worn by the male aristocracy of the Heian Period (794-1185), and the outdated sōhatsu hairstyle. He was occasionally ridiculed for this outfit, but nevertheless, the pride he took in wearing this attire was clearly reflected in his facial expression.

From 1858, Kuniomi sided with SAIGŌ Takamori, Gesshō, and other imperialists. Despite the shogunate’s awareness of its impending doom, to turn against the ruling political establishment was nevertheless a crime, and Kuniomi was arrested and imprisoned a number of times. Kuniomi was also an accomplished poet, and he often inveighed his poems with despair and hope, many of these works still famous today for their ability to move the reader.

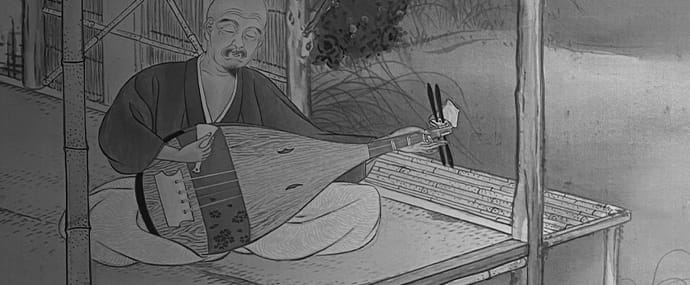

HIRANO Kuniomi was also an accomplished performer of the ichigenkin, a monochord known during the Heian Period, but later forgotten. This ballad mentions his abilities with this instrument in a very positive light. In the early 19th century and the beginnings of a classicist revival movement, the instrument and its music were resurrected by those who idealized the refined life of Heian court culture, and attempted to recreate this elegance through the performance of this simple, yet gracious instrument. Given the association of this instrument with court culture and imperial rule, Kuniomi’s attraction to this instrument would appear self-evident.

Synopsis

In the late summer heat of 1864, the fervent imperialist HIRANO Kuniomi lingered in a Kyoto prison. He had the nominal support of SAWA Nobuyoshi, who had been associated with the troops of the Chōshū fief. The Chōshū-people supported the restoration of imperial rule, which was finally realized in 1867 with the Meiji Government. Kuniomi had fought in Ikuno, Hyōgo prefecture, and then fled to Izushi (Toyo’oka city), where he was captured, brought to Kyoto and then incarcerated in the Rokkaku Prison.

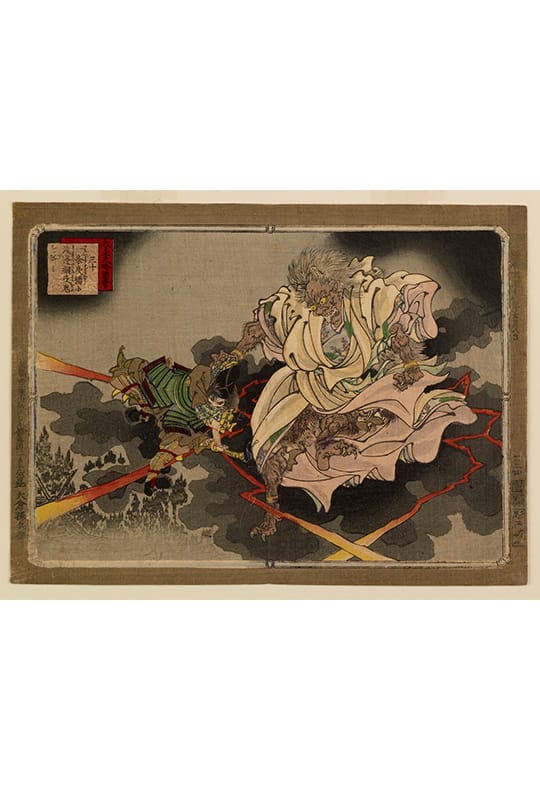

When distracting himself from the miserably hot and humid conditions of the prison and the mosquitoes by performing the ichigenkin and reciting his own poetry, he suddenly heard battle cries. In an attempt to reach the Imperial Palace, Chōshū troops had entered the Capital when they encountered the shogunate palace guards with whom they subsequently engaged in battle.

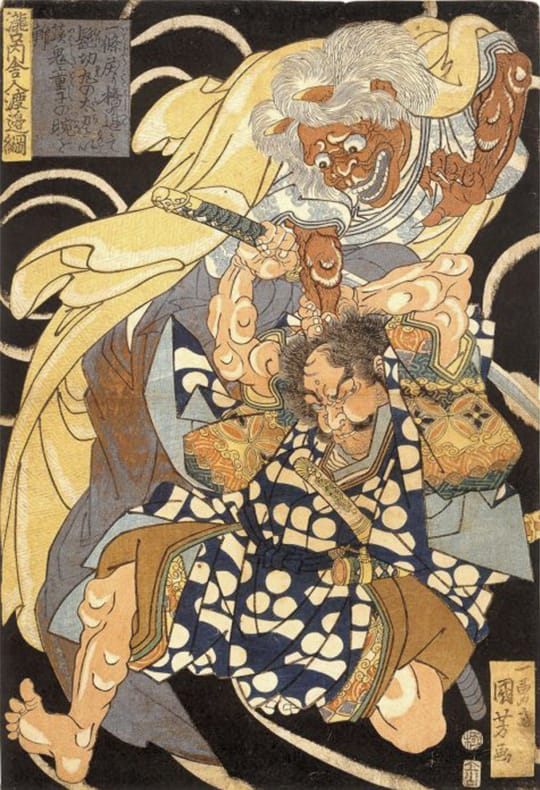

In situations such as this, prisons were opened and the prisoners set free in order to prevent them from perishing in the fires that resulted from firearm exchange and other struggles. Many of the inmates were able to flee; however, the prison guards attacked Kuniomi and thirty-three other incarcerated men. An impassioned exchange of reproaches begins between Kuniomi and his guards, and despite Kuniomi’s bravely grasping the spears of the attacking guards in front of his bare chest he finally had to succumb. He prostrated himself in prayer for the Emperor, and then allowed the guards to stab him fatally.

Lyrics

-

1. The cherry trees of the Ninefold Palace are buffeted in the breeze, Im Palast, wo Kirschbaumblüten sich im Winde wiegen,

Kokonoe no mihashi no sakura kaze soyogi 九重の御階の桜風戦ぎ

-

2. wandering to and fro in this world with the nightingale’s song, hat ein Ritter oft dem Nachtigallen-Schlag gelauscht

yo o uguisu no naku koe ni 世を鶯の鳴く声に

-

3. The bamboo flute once played, und sich dem Müßiggang ergeben.

kayoite fukeru fuetake o 通ひて吹ける笛竹を

-

4. is suddenly discarded by the warrior. Doch nun wirft er seine Flöte weg.

niwaka ni sutete masurao no 俄かに捨てて益良雄の

-

5. Girt with his sword, thoughts of country Er greift zum Schwert und denkt voll Leidenschaft,

torihaku tachi ni shikishima no 取り佩く太刀に敷島の

-

6. and the spirit of Japan lie nestled in his breast. wie er wohl seinem Vaterlande helfen könnte.

yamatogokoro zo komoruran 大和心ぞ籠るらん

-

7. And so, the patriot from Chikuzen, Dieser Mann aus Chikuzen, ein wahrer Patriot –

sate mo Chikuzen no shishi さても筑前の志士

-

8. HIRANO Jirō Kuniomi, HIRANO Jirō Kuniomi –

HIRANO Jirō Kuniomi wa 平野次郎国臣は

-

9. while protecting his lord, SAWA Nobuyoshi, wollte seinen Herrn, Fürst SAWA Nobuyoshi, schützen,

SAWA Mondo Nobuyoshi kyō o yōshitsutsu 沢主水宣嘉卿を擁しつゝ

-

10. with those nationalists loyal to the emperor against the shogunate, und so zog er mit den Kaisertreuen gegen die Armee des Shoguns

kinnō jōi tōbaku no 勤王攘夷討幕の

-

11. in the mountain winds of Ikuno, their flag in den Krieg und ließ die Flaggen flattern im Gebirg von Ikuno.

hata o Ikuno no yamakaze ni 旗を生野の山風に

-

12. fluttered pitifully, Doch schmerzlich war es anzusehn,

hirugaeshitaru kai mo naku 翻へしたる甲斐もなく

-

13. and vanished like the clouds and mists, they were overwhelmed, als diese bald verschwanden so, wie Wolkendunst sich auflöst.

unka no gotoku oshiyoseshi 雲霞の如く押寄せし

-

14. crushed by the strength of their assailants. Alle Kaisertreuen mussten vor dem Feinde weichen,

utte no sei ni yaburarete 討手の勢に破られて

-

15. Nothing could be done, and enduring their bitterness nichts mehr konnten sie erreichen,

yaru kata mo naki munensa o 遣る方もなき無念さを

-

16. they fled to Izushi. und so flohen sie nach Izushi.

shinobite Izushi e ochikeru ga 忍びて出石へ落ちけるが

-

17. Soon after, captured by the enemy, Kuniomi nahm man aber bald gefangen,

hodo naku teki ni toraerare 程なく敵に捕へられ

-

18. to Rokkaku Street in the Capital, überführte ihn nach Kyoto

miyako ōji wa Rokkaku no 都大路は六角の

-

19. and in the dark prison there, he was placed, in das Rokkaku-Gefängnis an der Sechsten Straße.

kuraki hitoya ni irerarete 暗き獄に入れられて

-

20. to spend the months and days simmering in resentment. Hier im Dunkeln brachte er so viele Tage, ja gar manchen Monat zu.

hifun no tsukihi okurikeri 悲憤の月日送りけり

-

21. It was the first year of the Ganji era Im Herbst des ersten Jahrs der Ganji-Zeit, da war’s am

koro shimo Ganji gannen no 頃しも元治元年の

-

22. and while it was the end of the 7th month and already autumn, Ende des Augusts noch unerträglich heiß.

aki to wa iedo fuzuki no sue 秋とはいへど文月の末

-

23. within the prison Im Kerker drückte schwül

hitoya no uchi wa nakanaka ni 獄の内はなかなかに

-

24. the heat remained. die fürchterlichste Hitze.

mada sariyaranu atsusa o ba まだ去りやらぬ暑さをば

-

25. To distract himself, Kuniomi Um sich abzulenken,

magirawasan to Kuniomi wa 紛らはさんと国臣は

-

26. plucked his sumagoto, and whispered zupfte Kuniomi sehnsuchtsvoll sein Monochord:

sumagoto hikite shinobine ni 須磨琴弾きて忍び音に

-

27. “How should I repel the mosquitos? “Wie soll ich mich mit Räucherwerk vor Mücken schützen,

kayari taku yoshi mo nakereba ikani sen 蚊遣り焚く由もなければ如何にせん

-

28. the fitful broken sleep of the summer nights” in der Nacht, die mich nicht schlafen lässt.”

i o ne wabinuru natsu no yonayona いをねわびぬる夏の夜な夜な

-

29. and as he was elegantly chanting So sang er voller Wehmut.

yukashiku utō orishimo are 床しく謡ふ折しもあれ

-

30. the sudden rumbling of cannon fire Plötzlich hörte er Gewehre donnern,

niwaka ni todoroku hōsei wa 俄かに轟く砲声は

-

31. shook both heaven and earth, die die Erde und den Himmel zittern machten,

tenchi yurugasu bakari nari 天地撼がすばかりなり

-

32. and from near and far, the sound of battle cries, und von nah und fern vernahm er Schlachtgeheul.

ochikochi kikoyuru toki no koe 遠近聞ゆる喊の声

-

33. roaring flames charred the skies, Der Himmel färbte sich glutrot,

mōka wa ten o kogashitsutsu 猛火は天を焦しつゝ

-

34. fanning the scorching winds and blaze, und heiße Winde trugen Riesenflammen

neppū kaen o fukiaori 熱風火焔を吹き煽り

-

35. in the direction of the palace, black smoke in die Richtung des Palasts –

dairi no kata ni kurokemuri 内裏の方に黒煙り

-

36. whirling and eddying horribly. in wilden Wirbeln – grässlich war das.

uzu makikakaru susamajisa 渦巻きかゝる凄まじさ

-

37. Kuniomi immediately looked towards the palace: Kuniomi schaute hin zum Hof des Kaisers:

Kuniomi sonata o kitto mite 国臣そなたを屹と見て

-

38. “With the deepest respect, your highness, „Mit Respekt will ich Euch fragen, meine Hoheit,

osore ōku mo ōgimi wa 畏れ多くも大君は

-

39. how are you faring? wie Ihr Euch befindet.

ikani watarase tamōran 如何にわたらせ給ふらん

-

40. Those with whom I have sworn oaths, Im Verband mit jenen, die Euch Treue schworen

chikaishi tomo wa ka no moto ni 盟ひし友は彼の下に

-

41. are assuredly serving as your shield in battle. wollte ich im Kampf Euch schützen.

mitate to narite tatakawan 御楯となりて戦はん

-

42. Ah, my fate is that of a zelkova bow, Doch mein Schicksal ist dem Ulmenbogen gleich,

aa wa ga un wa tsukiyumi no あゝ我が運は槻弓の

-

43. broken and discarded, a transient outcome.” zerbrochen, weggeworfen.”

orisuterareshi hakanasa to 折り捨てられしはかなさと

-

44. He closed his eyes for a moment. Eine Weile schloss er seine Augen.

shibashi manako o uchifusagi 暫し眼を打塞ぎ

-

45. “Having placed myself in the dragon’s claws and the tiger’s maw, „In die Drachenklauen, ins Gebiss des Tigers hab’ ich mich gewagt,

ryūkyō kokō kono mi o yosu 龍鋏虎口斯身ヲ寄ス

-

46. half my life within an ambitious dream, mein ganzes Leben war ich – wie im Traume – nie verzagt.

hansei no kōmyō ichimu no uchi 半世ノ功名一夢ノ中

-

47. someday when my bones are buried in the netherworld, Einmal werden meine Überreste Ruhe finden –

tajitsu kyūsen hone o uzumuru tokoro 他日九泉骨ヲ埋ムル処

-

48. it will be as someone condemned, my faithfulness unacknowledged.” dass dann meine Treue nicht erkannt war, kann ich nicht verwinden.

keiyo tare ka mata kochū o mitomen “刑余誰カ又孤忠ヲ認メン

-

49. He hummed this Chinese poem. Leise sang er dieses Lied aus China,

kuchizusamikeru karauta ni 口吟みける唐歌に

-

50. The upright heart of this brave and stalwart man, mutig und beherzt als Mann

masuratakeo no isagiyoku 益良猛雄の潔よき

-

51. fully aware of his resolution. mit klarem Geist.

kakugo no hodo koso shirarekere 覚悟の程こそ知られけれ

-

52. The scarlet flames raged with greater ferocity, Die Flammen wurden immer röter, immer wilder,

guren no mōka en’en to 紅蓮の猛火炎々と

-

53. drawing near the prison. kamen drohend dem Gefängnis nahe.

hitoya majikaku moesemaru 獄間近く燃え迫る

-

54. To spare them from the peril, the gates Um das Leben der Gefangenen zu schonen,

kinan sakeyo to rōmon o 危難避けよと牢門を

-

55. were opened, and they freed prisoners öffnete der Kerkermeister zwar die Pforten,

hirakite hanatsu meshiudo no 開きて放つ囚人の

-

56. under the watchful eyes of the guard. ließ jedoch die Inhaftierten beim Verlassen kontrollieren.

naka o nirande hitoyamori 中を睨んで獄守

-

57. “HIRANO Kuniomi, stop!” „ HIRANO Kuniomi, halt!“

HIRANO Kuniomi todomare to 平野国臣止まれと

-

58. one shouted in a huge voice. schrie laut ein Wächter.

iratakagoe ni yobawattari 苛高声に呼はったり

-

59. But he had been expecting this, Kuniomi hatte dies erwartet

kanete goshitaru kotonareba 予て期したる事なれば

-

60. and he neither moved nor paled, und verlor die Fassung nicht.

sara ni dōzuru keshiki naku 更に動ずる気色なく

-

61. but once again plucked his ichigenkin: Er setzte sich gelassen vor sein Monochord.

mata sumagoto o kakinarashi また須磨琴を搔き鳴らし

-

62. “The great tree blocking the heavenly light will shortly, „Große Bäume sind den Sonnenstrahlen hinderlich,

amatsuhi o ōu ōgi mo shibashi nite 天津日を掩ふ大樹も暫しにて

-

63. both branches and leaves, wither. Geäst und Laub verwittern.

tsui ni eda ha mo karehatenu beshi つひに枝葉も枯れ果てぬべし

-

64. Naught but dew on the grass, our lives vanish into emptiness.”ware wa motoyori kusatsuyu no Flüchtig wie der Tau auf Gräsern schwindet unser Leben.“

kiyubeki inochi nani ka sen われは固より草露の消ゆべき命何かせん

-

65. Those who betrayed the Emperor, Jene, die Verrat am Kaiser übten,

Ōuchiyama no gyakuzoku no 大内山の逆賊の

-

66. with lusty voices. schrien laut

koe ni chikara no komoru toki 声に力の籠る時

-

67. A number of rowdy warriors approached: und stürmten wild heran.

kakeyoru sunin no arakure bushi 駆け寄る数人の荒くれ武士

-

68. “Silence, Kuniomi, you yourself „Halt dein Maul jetzt, Kuniomi,

damare Kuniomi nanji koso 黙れ国臣汝こそ

-

69. are a traitor ignorant of gratitude ein Verräter bist du, ohne Dankgefühle

ongi shirazaru daigyakunin 恩義知らざる大逆人

-

70. for the TOKUGAWA regime and its authority. für den Segen unsrer TOKUGAWA Obrigkeit.

TOKUGAWA bakufu no goikō o 徳川幕府の御威光を

-

71. We will have you know this! Prepare yourself!” Wir werden es dir zeigen, sieh dich vor.“

omoishirasuzo kannen seyo to 思い知らすぞ観念せよと

-

72. They rushed forward, their spears aimed at him, Sie rannten mit gezückten Speeren auf ihn los.

tsukikuru yari no kera kubi o 突き来る槍のけら首を

-

73. Which he seized, and made them unable to move. Doch Kuniomi fing die Waffen ab und konnte sie blockieren.

munzu to tsukande ugokasazu むんづとつかんで動かさず

-

74. “You ruffians, who do you think you are! „Grobe Kerle, wisst ihr, was und wer ihr seid?

onore rōzeki nani mono zo おのれ狼藉何ものぞ

-

75. The TOKUGAWA have turned their backs to heaven and Die TOKUGAWA Herrscher haben sich dem Himmel widersetzt

ten ni somukeru TOKUGAWA ni 天に背ける徳川に

-

76. they spur you on. und haben euch verführt.

karitsukawaruru nanjira koso 駆使はるゝ汝等こそ

-

77. You yourselves are dogs ignorant of the Emperor’s favours. Ihr selber zollt dem Kaiser keine Achtung, Hunde seid ihr.

kōon shiranu inuzamurai 皇恩知らぬ犬士

-

78. I am now here, and face my unfortunate end, Hier bin ich und spüre, wie mein Tod

ware ima koko ni un tsutanaku 吾れ今こゝに運拙なく

-

79. pierced by wicked spears, durch eure Speere naht.

mudō no yari ni sasaru tomo 無道の槍に刺さるとも

-

80. but my soul will remain Mein Herz jedoch bleibt stark

konpaku nagaku todomarite 魂魄永く留まりて

-

81. with my desire to protect the emperor!” im Wunsch, den Kaiser zu beschützen.“

sumeramikado o mamoran to 天皇を護らんと

-

82. Facing the Palace, he prostrated himself in prayer. Zum Palaste hingewendet warf er sich zu Boden,

dairi no kata o fushiogami 内裏の方を伏し拝み

-

83. He finally bared his chest, Danach machte er die Brust frei:

yagate munamoto kutsurogetsu やがて胸元くつろげつ

-

84. “Stab me here”, and when he sat upright, „Stecht nur zu!“ rief er der Horde aufrecht sitzend zu.

koko o tsuke tote inaoreba こゝを突けとて居直れば

-

85. they lunged, thrusting their spears into the brave man. So rammten sie denn ihre Speere in die Brust des Helden.

kuridasu hosaki ni masurao no 繰り出す穂先に丈夫の

-

86. A loyal soul such as this will never be seen again. Einen derart edlen Treuen wird es nie mehr geben auf der Welt.

chūkon kaerazu narinikeri 忠魂還らずなりにけり

-

87. “The Flowers’ guardsman, „Am Hofe möchte ich

Ōuchiyama no hanamori ni 大内山の花守に

-

88. I would love to become”, he sings. die Blumen pflegen“, sang er.

mi o ba nasan to utaiteshi 身をはなさんと歌ひてし

-

89. His elegant sentiments, in this confused disturbed world Solch ein feiner Geist hat wahrlich keinen Platz in dieser rauhen Welt,

miyabigokoro mo karigomo no 風流心も刈菰の

-

90. no longer can be appreciated er wird nicht mehr so hochgeschätzt, wie seine Taten es verdienten.

midaretsuru yo wa itoma dani 乱れつる世は暇だに

-

91. the raging storm sweeping vanished with Wirbelnd fegen Stürme

arashi fukishiku miyakoji no 嵐吹きしく都路の

-

92. the dew on the streets of the capital. And in his homeland, durch die Straßen in der Kaiserstadt.

tsuyu to kieshi mo furusato no 露と消えしも故郷の

-

93. Chiyo no Matsubara, throughout the ages, In Chiyo no Matsubara, in seiner Heimat

Chiyo no Matsubara chiyo kakete 千代の松原千代かけて

-

94. his name will remain the sweetest of fragrances. wird jedoch sein Name ewig Wohlklang sein,

nokoru sono na zo kaguwashiki 残る其名ぞかぐはしき

-

95. his name will remain the sweetest of fragrances. sein Name ewig Wohlklang sein.

nokoru sono na zo kaguwashiki 残る其名ぞかぐはしき

Notes

7. Chikuzen… This is the ancient name for the western part of present-day Fukuoka prefecture in Kyūshū. 8. HIRANO Jirō Kuniomi… (details: see introduction to the piece) 1828-1864. He is usually referred to as HIRANO Kuniomi, and occasionally simply as Kuniomi. His name has a nationalistic flavor as the characters literally mean “Vassal of the Land”. 9. SAWA Nobuyoshi…1836-1873. He was the head of a rebellious group of which HIRANO Kuniomi was the actual leader. He belonged to the anti-shogunate Imperial Restoration Party, and was later a member of the Meiji Government. 11. Ikuno… Ikuno is the present-day Ikunochō district in central Hyōgo Prefecture. 16. Izushi… Izushi is nowadays part of Toyo’oka City in Hyōgo prefecture. 18. Rokkaku… This is the name of a street in Kyoto, once famous for its prison in which rebellious samurai were incarcerated. 26. Monochord… The Japanese monochord is a single-stringed zither known as the ichigenkin (or sumagoto). Tradition holds that while Kuniomi was in prison, an unlikely environment to have access to an instrument, that he extracted a thread from his straw mat and fixed it to a board of his cell wall, and thus created a substitute, if nonetheless primitive one, for his delicate musical instrument. 32. Battle cries… The battle was between the Chōshū (present-day Yamaguchi Prefecture) forces supporting the Emperor, who had mounted a surprise entrance into the Capital, and the shogunate forces guarding the palace. 87… The following lines are from a waka Kuniomi had composed on New Year’s Day of 1863 when he was in the Masugiya Prison in Fukuoka. 93. Chiyo no Matsubara… This refers to a famous place outside the Fukuoka City center where in 1869 a monument to Kuniomi was erected commemorating this loyal servant of the Emperor.

Music Notes

HIRANO Kuniomi is the tale of a devoted follower of the Imperial Restoration Movement. It opens unconventionally as the first line clearly differs from the melodies that usually start a ballad. The immediate mention of the Imperial Palace may account for this as any reference to the Imperial Palace, a dwelling that inspires the hero’s deepest admiration, requires something different from the normal introduction.

An especially attractive musical aspect of this piece is its treatment of another musical instrument. In line 26, a single-stringed instrument, the sumagoto, is mentioned and then followed by an interlude called Sumagoto ichi. The name of this monochord, correctly known as the ichigenkin, refers to an instrument the Heian period nobleman, ARIWARA no Yukihira (818-893), is said to have created to dispel his loneliness when at Suma Bay. The legend claims that when alone on the shore, he found a board to which he attached a string. By pressing his left-hand finger at different points and plucking with his right hand, he produced different sounds, and could perform melodies, and thus soothe his melancholy.

When HIRANO Kuniomi, a poet and an accomplished ichigenkin-player (a neoclassic fashion at this time), was in prison, he assuredly had no proper musical instrument, and like the earlier ARIWARA no Yukihira, he managed to obtain a board and mount a string of some sort, and thus create an instrument similar to a zither.

In the biwa interlude Sumagoto ichi, this monochord is imitated on the chikuzen biwa. The mood is also sad and forlorn, which is realized by primarily using the subdued 4th string rather than the more brilliant 5th string, which is commonly used for the melody.

In the lines 27 and 28 a waka is sung. This poem is followed by an interlude known as Imayō kyoku. Originally, imayō was a popular vocal genre during the Heian Period (794-1185). Later, the term Imayō kyoku referred to Chikuzen imayō, a piece that shares the same melody as Kurodabushi, a well-known song glorifying a 16th century hero from the Chikuzen region. The melody for Kurodabushi, however, derives from Etenraku, a representative work of gagaku, music of the imperial court. This again creates the appropriate aesthetic for Kumiomi’s imperial tastes.

Before singing another waka in lines 62-64, there is a second interlude that imitates the ichigenkin: Sumagoto ni. Here, a medieval atmosphere is conveyed at the beginning by playing the 4th and 5th strings, a unison, and the 3rd string, which is a fifth lower. The three pitches sounded together on the biwa create an archaic atmosphere, and the listeners may immediately associate this resonance with the Heian Period.