The Tale of the Heike-search

Kyoto-search

miyako ochi

都落ち

Introduction

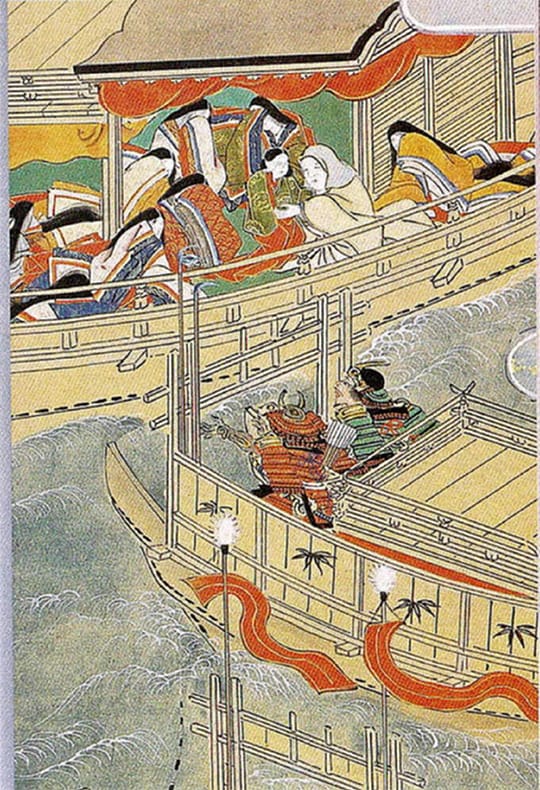

In 1183, the GENJI general, Kiso Yoshinaka, fought several battles against the HEIKE armies in the Hokuriku region (present-day prefectures of Fukui, Ishikawa and Toyama). Victorious in all these struggles, he moved towards Kyoto. The HEIKE, fearing his power, left the capital for good on the 14th day of the 8th month in 1183, and moved to the West.

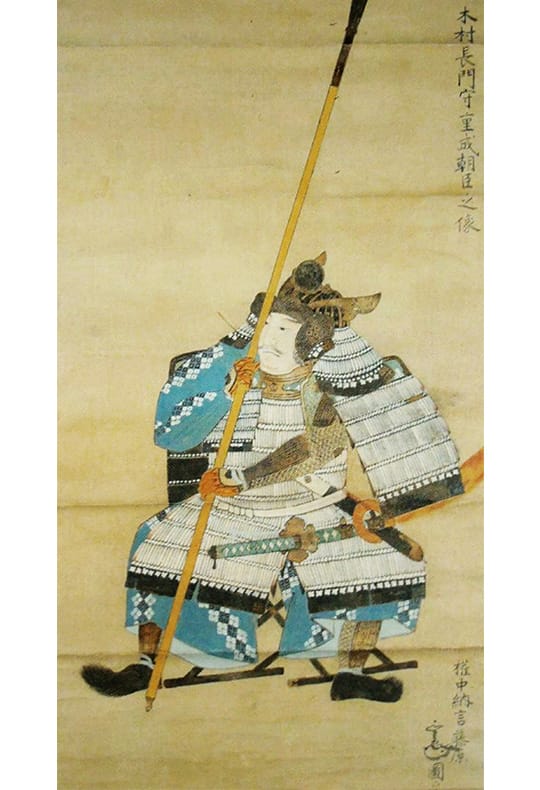

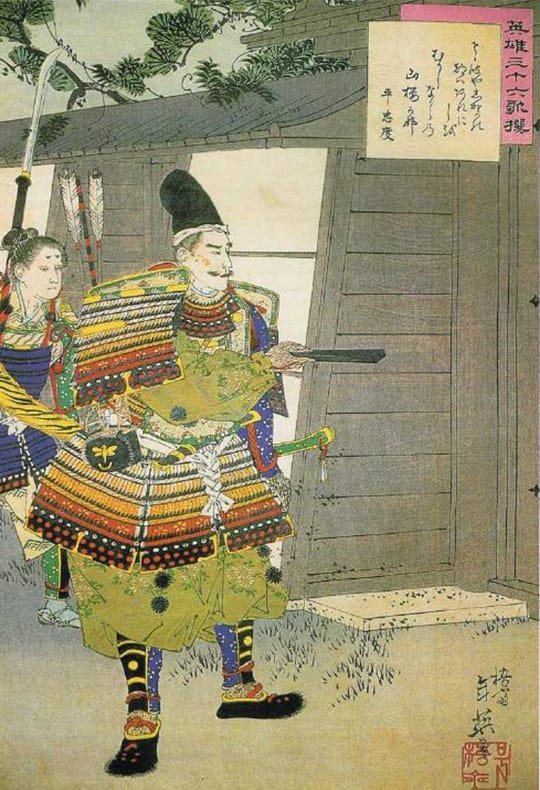

In the Tale of the Heike there are many sad and moving stories about HEIKE leaders during this forced departure from the capital. One of the best known is the story of Tadanori (1144-1184). This high-ranking HEIKE general had been studying waka poetry under the nobleman, FUJIWARA Shunzei (1114–1204), for a long time.

In 1183, FUJIWARA Shunzei had been instructed to compile an imperial poetry anthology. Because of the ongoing war, the editing process, however, had to be postponed. Tadanori nevertheless deeply wished that with the resumption of the editing of the poetry collection, one of his poems would be included in the anthology; accordingly, he brought his best poems to Shunzei. This editor chose one and included it later in the Senzai wakashū, a collection of 20 scrolls of 1285 waka poems.

Since the editing could only be finished after the war, the authorship of Tadanori had to be suppressed as the HEIKE were immediately considered enemies of the throne with their defeat. Tadanori’s contribution was therefore included as a poem “by an anonymous poet.”

The scene of Tadanori visiting Shunzei on the night the HEIKE left from Kyoto is fiction. Many different versions of the Tale of the Heike include a section entitled Shibukassenjō, which recounts a different rendition of Tadanori’s visit. According to the Shibukassenjō, Shunzei was at that time too afraid to meet his poetry student as he was a member of the HEIKE clan. He therefore did not open the gate for him. Tadanori had no other choice but to throw the scroll with his poems over the wall towards Shunzei’s residence where it was picked up. Years later, somebody created the moving story of the two men’s meeting seen in this ballad.

Synopsis

The wars between the GENJI and the HEIKE ended in 1185 with the sea battle of Dannoura in the West of Japan. For several generations, the HEIKE had been extremely influential in Kyoto with their family ties to the Imperial Court. But when the GENJI approached the capital, the HEIKE burnt their residences in the Rokuhara district of Kyoto and moved westwards.

On the evening of their departure, the younger brother of the HEIKE clan leader Kiyomori, TAIRA no Tadanori, used the dark of the night to return once more to Kyoto in order to visit FUJIWARA Shunzei. This nobleman living in the Gojō Avenue was responsible for the compiling and editing of an imperial anthology of poems. Tadanori fervently wished to have one of his poems included in the anthology. Should he be awarded this honor, he would be freed of any fear of dying in one of the forthcoming battles. Shunzei was deeply moved and assured him that he would fulfill Tadanori’s wish, and bid him farewell with tears in his eyes.

After the elaborate delivery of this poem, the ballad concludes with observations on the immortality of poetry and the evanescence of a poet’s life.

Lyrics

-

1. The sound of the Gion Shōja bell Der Glockenklang von Gion Shōja

Gion Shōja no kane no koe 祇園精舎の鐘の声

-

2. echoes the impermanence of all things. kündet von der Nichtigkeit des Tuns in dieser Welt.

shogyō mujō no hibiki ari 諸行無常の響あり

-

3. The color of the sala flowers Die sala Blüte weist mit ihrer fahlen Farbe

sara sōju no hana no iro 沙羅双樹の花の色

-

4. reveals the truth that the prosperous must decline. auf Verderben und Verfall von Ruhm und Glanz.

jōsha hissui no kotowari o arawasu 盛者必衰の理を表す

-

5. With the nine-fold clouds of cherries in full bloom, Die Kirschbaum-Pracht glich Wolkennebeln

kokonoe no kumoi ni magō hanagasumi 九重の雲井にまがう花がすみ

-

6. everybody in the capital und verzauberte die Hauptstadt Kyoto.

Kyō no miyako o waga yo to zo 京の都をわが世とぞ

-

7. flushed with the abundance of lovely sake, Reichlich floss der Sake,

eiga no bishu ni eishirete 栄華の美酒に酔ひ痴れて

-

8. was dozing with the impassioned dreams of beautiful lovers. und man gab sich Träumen hin von Liebeslust und Freude.

fuzan no yume ni utatane no 巫山の夢にうたゝ寝の

-

9. Such were the lives of the arrogant Heike clan in Rokuhara. Herrlich war das Leben für die stolzen Heike in den Villen von Rokuhara.

ogoru Rokuhara HEIKE no ichimon 驕る六波羅平家の一門

-

10. But suddenly at dawn Doch an einem frühen Morgen

orishimo are ya akatsuki no 折しもあれや暁の

-

11. battle cries rocked their pillows, wurden sie erschreckt von Kampfgeschrei,

makura o yusuru toki no koe 枕をゆする鬨の声

-

12. rumbling like thunder. das laut wie Donner grollte.

rai no gotoku ni hibiku nari 雷の如くに響くなり

-

13. The men of MINAMOTO no Yoritomo, Waren das nicht Yoritomos Männer?

kore zo Uhyōenosuke MINAMOTO no Yoritomo ga これぞ右兵エ佐源の頼朝が

-

14. waving their white flag dyed with the bamboo gentian crest schwarze Bambus-Enziane zierten ihre weißen Flaggen,

sasarindō no mon somete 笹竜胆の紋そめて

-

15. under the moon and the stars of a clear night, die im Dunkeln leuchteten wie Sterne.

kakaguru shirahata hoshizukiyo 掲ぐる白旗星月夜

-

16. had assembled in the hills of Kamakura In den Hügeln von Kamakura formierten sich (vor langer Zeit) Verbände.

Kamakurayama ni oshitatete 鎌倉山におし立てゝ

-

17. where horses neighed and warriors showed their bravery. Pferde wieherten und GENJI Krieger probten ihren Mut,

gunba inanaki hei isami 軍馬嘶き兵勇み

-

18. Their fierce attacks were avalanches. um später wie Lawinen loszubrechen.

nadare o utte semenoboru 雪崩を打って攻め上る

-

19. When the fowl in the Fuji River fled the water’s edge, In der Schlacht am Fuji-Fluss, da ließen sich die HEIKE

Fujigawaberi no mizudori no 富士川辺の水鳥の

-

20. their wings raucously clapping the river’s surface, von dem bloßen Lärm verschreckter Wasservögel täuschen,

haoto ni ukitatsu akahata wa 羽音に浮き立つ赤旗は

-

21. the HEIKE took fright and scattered in the winds without a trace. und zerstoben angsterfüllt in alle Winde.

kaze ni tobichiri kage mo nashi 風に飛び散り影もなし

-

22. And in the pass of Kurikara, the “fire bulls incident” Auf dem Pass von Kurikara stifteten die “Feuer-Rinder” Chaos –

Kurikara tōge no kagyū no kei くりから峠の火牛の計

-

23. caused the northern guard to collapse. Niederlage war die Folge, und so brach im Norden aller Widerstand.

kita no mamori wa tsuie hate 北の守りは潰え果て

-

24. The GENJI general Kiso Yoshinaka attacked Der GENJI General Kiso Yoshinaka nutzte dies

Kiso GENJI no taigun wa 木曽源氏の大軍は

-

25. with his huge army advancing in waves like the ocean. und stieß mit seinen Truppen vor wie eine Meereswoge.

ushio o nashite semariyose 潮をなして迫りよせ

-

26. Finally, he rode into the capital after crossing the Ōsaka pass. Angekommen auf dem Pass von Ōsaka, formierten sich die Reiter.

Ōsakayama ni koma o tatsu 逢坂山に駒を立つ

-

27. There, the HEIKE, in their arrogance, thought Weil die arroganten HEIKE fest der Meinung waren,

katte wa HEISHI ni arazunba かっては平氏に非ずんば

-

28. ‘not being HEIKE’ meant ‘not being human’. ‘wer nicht HEIKE ist, der ist kein Mensch’,

hito ni arazu to gōgoseru 人に非ずと豪語せる

-

29. But now, these princes of the Flower Capital, zerstörten sie mit Feuerbränden in der Blütenhauptstadt

hana no miyako no HEIKE no kindachi 花の都の平家の公達

-

30. set fire to their mansions in the Rokuhara district. ihr Quartier von Rokuhara.

ima wa tada Rokuhara yakata ni hi o hanachi 今はたゞ六波羅館に火を放ち

-

31. With the flames like flowers at their backs, Und so waren rote Flammen jetzt die Blumen (ihres Abschieds),

honoo to hana o se ni abite 炎と花を背に浴びて

-

32. they departed on their final journey, never to return, als sie schnell die Stadt verließen, ohne je zurückzukehren.

nido to kaeranu shide no tabi 二度と帰らぬ死出の旅

-

33. abandoning the capital, fleeing to the western seas, Atemlos in Richtung Westen stürzten sie davon

miyako o sutete saikai e 都をすてゝ西海え

-

34. flight having become their fate. und lieferten sich einem ungewissen Schicksal aus.

nogare hashiru mo sadame nari 逃れ走るも運命なり

-

35. The younger brother of Kiyomori, Doch da war Kiyomoris jüngrer Bruder,

koko ni Kiyomorikō no onshatei nite こゝに清盛公の御舎弟にて

-

36. Tadanori, the lord of Satsuma, Tadanori, Herr von Satsuma.

Satsumanokami Tadanorikō wa 薩摩の守忠度公は

-

37. accompanied by several horsemen, Mit wenig Reitern im Gefolge

tomo no sūki o shitagaete 供の数騎をしたがへて

-

38. riding along the Yodo river in the dark of night, machte er in tiefer Nacht am Yodo-Ufer kehrt

Yodo no kawabe no yoiyami ni 淀の川辺の宵闇に

-

39. suddenly turned back to the capital. und ritt zurück nach Kyoto.

magirete miyako ni hikikaeshi まぎれて都に引き返し

-

40. The aim of his secret journey Im Geheimen suchte er

hiso to otonuru sono saki wa ひそと訪ぬるその先は

-

41. was to visit FUJIWARA Shunzei, a courtier of the third rank den Fürsten FUJIWARA Shunzei auf,

Sanmi FUJIWARA Shunzeikyō no 三位藤原俊成卿の

-

42. whose residence was located on Gojō Avenue. in dessen Villa an der Fünften Straße.

Gojō no yakata to oboetari 五条の館とおぼえたり

-

43. Tadanori drew near Shunzei, and said, Tadanori trat vor Shunzei:

Tadanorikō wa Sanmi no mae ni ayumi yori 忠度公は三位の前に歩みより

-

44. “Should this world once again know peace and you fulfill your commission to compile

yo shizumari sōrawaba “Kommt der Frieden wieder in die Welt, dann werdet Ihr, wie ich vernommen,

-

45. the imperial poetry anthology of which I have heard, eine Kaiserliche Sammlung von Gedichten kompilieren.

Chokusen kashū no gojō kudaru to uketamawaru 勅撰歌集の御定下ると承る

-

46. it would be the highest honor, Ehr und Glück in höchstem Maße wären mir beschieden,

waga shōgai no menmoku ni 我が生涯の面目に

-

47. if one of my poems should find his lordship’s approval wenn ein einziges Gedicht von mir

isshu nari tomo shinokimi no 一首なりとも先生の

-

48. and be included in the collection. This would make me deeply happy.” in diese Sammlung aufgenommen würde.”

goon o ukureba saiwai nite sōrō to 御恩を受くれば幸にて候と

-

49. From beneath his armor Und aus einer Faltentasche seiner Rüstung

yoroi no hikiawase yori 鎧の引き合せより

-

50. he withdrew a scroll, zog er eine Rolle,

makimono hitotsu toriidashi 巻物一つ取り出だし

-

51. and shedding tears, humbly presented it with both hands. die er ehrfurchtsvoll mit Tränen in den Augen seinem Lehrer überreichte.

sasaguru mite ni chiru namida 捧ぐる御手に散る涙

-

52. Shunzei, seeing this poem said, Shunzei war gerührt und sagte:

Sanmi no kyō wa sore o kiki 三位の卿はそれをきゝ

-

53. “when the time comes, “Wenn die Zeit gekommen ist,

sarubeki toki no kitarinaba さるべき時の来りなば

-

54. I shall unfailingly fulfill your wish.” soll Eurem Wunsch entsprochen werden.”

kanarazu gyoi ni soimōsubeshi to 必ず御意に副ひ申すべしと

-

55. Hearing these words, Als nun Tadanori diese Antwort hörte,

kotaekereba 答へければ

-

56. Tadanori was delighted. war er überglücklich.

Tadanorikō wa yorokobite 忠度公はよろこびて

-

57. “Should I drown and perish in the waves of the Western Sea, “Ob im Westen ich im Meer ertrinke

ima wa Saikai no nami ni shizumaba shizume 今は西海の波に沈まば沈め

-

58. or should my corpse be lost in the mountains’ depths, oder in den Bergen namenlos zugrunde gehe,

san’ya ni kabane o sarasu tomo 山野に屍をさらすとも

-

59. I shall have no regrets.” all das macht mir keine Sorgen mehr.”

omoi oku koto sara ni nashi to 思い置く事更になしと

-

60. As he was leaving for the West: Gleich machte er sich auf in Richtung Westen.

nishi o sashite susumitsutsu 西を指して進みつゝ

-

61. “The journey ahead is long, and my thoughts wander “Meine Reise ist noch weit,

zento wa hodo tōshi omoi o 前途は程遠し思ひを

-

62. towards the distant goal in the evening clouds of Goose Mountain,” die Abendwolken auf dem Gänseberg geleiten mich zum Ziel.“

Gansan no yūbe no kumo ni hasu 雁山の夕べの雲にはす

-

63. he hummed to himself. Das summte er, und Shunzei

to kuchizusameba Shunzeikyō wa と口ずさめば俊成卿は

-

64. Shunzei saw him off in tears. wünschte ihm mit feuchten Augen Lebewohl zum Abschied.

namida o nagashite miokuri tamou 涙を流して見送り給う

-

65. “In Shiga, the capital of the rippling water lies in ruins, Kleine Wellen spielen am Gestade der zerstörten Stadt von Shiga

sazanami ya Shiga no miyako wa arenishi o さゞ波や志賀の都は荒れにしを

-

66. yet the mountain cherries bloom as ever!” doch wie früher werden dort die Kirschen wieder blühen.”

mukashinagara no yamazakura kana 昔ながらの山ざくらかな

-

67. The Path of Poetry is beautiful Lieder dichten ist ein wundervoller Pfad der Edlen,

geni uruwashiki uta no michi 実に麗はしき歌の道

-

68. even if the human body walks the road of transience. Körper sind vergänglich.

mi wa tatoe horobi no michi o ayumu tomo 身はたとへ滅びの道を歩むとも

-

69. Devoted to poetry, doch ein Kriegerherz, das sich der Dichtung widmet,

uta ni takusuru mononofu no 歌に託する武士の

-

70. the heart of this warrior glimmers in the waters of Lake Biwa. wird den See von Shiga überstrahlen,

kokoro wa Shiga no umi ni hae 心は志賀の湖に映え

-

71. The ineffable refinement of this departed poet und wir werden seiner Trefflichkeit gedenken

nokoseshi hito no yukashisa o 遺せし人のゆかしさを

-

72. will assuredly linger throughout the ages, bis in alle Ewigkeit

towa ni tsutaete kaoruran 永久に伝へて香るらん

-

73. will assuredly linger throughout the ages. bis in alle Ewigkeit.

towa ni tsutaete kaoruran 永久に伝へて香るらん

Notes

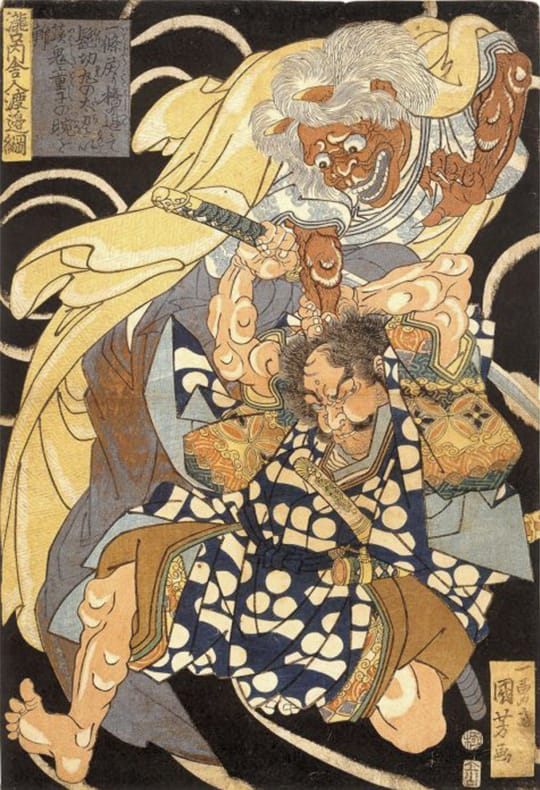

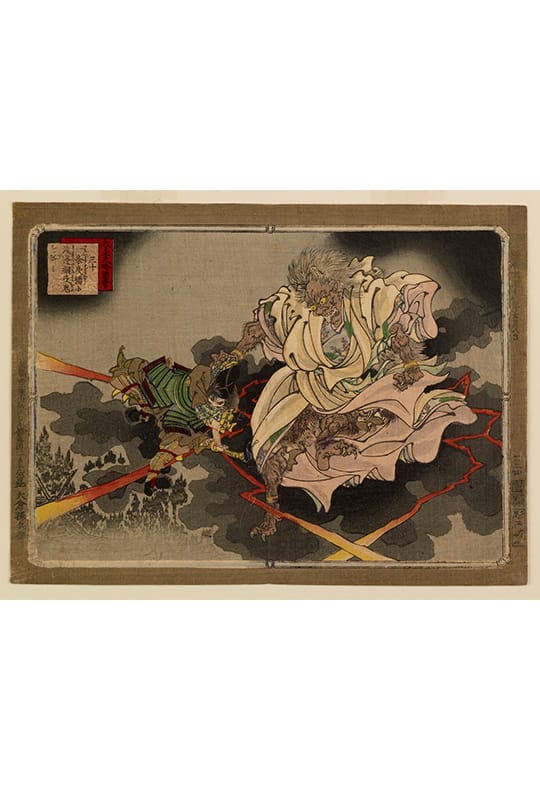

1.-4. The first four lines embody the essence of the Tale of the Heike, the monumental story of the rise and fall of the TAIRA clan in Kyoto. 1. Gion Shōja bell…Gion Shōja was a temple in northwestern India. This temple also functioned as a hospital, and when one of the patients was about to die, the temple bell rang of its own accord. 2. impermanence…Hearing the tolling of this bell helped the moribund to forget their pains, as it promoted reflection upon the impermanence of this world. 3. sala flower…This delicate flower blooms on a tree resembling an evergreen oak. When the Buddha died, it is said that the sala flowers turned white. 9. Rokuhara… This is a district in the Eastern Part of Kyoto, where many HEIKE families had their residences. 13. MINAMOTO no Yoritomo…MINAMOTO no Yoritomo (1147-1199), the Supreme Leader of the GENJI clan, stayed in Kamakura throughout the Genpei wars. 14. Bamboo-gentian crest…The crest of the Seiwa GENJI clan. 16. Kamakura…The GENJI headquarters close to present-day Tokyo. 19.-21. Fuji river… In 1180, the “Battle of the Fuji River” occurred between the GENJI and the HEIKE. Before the GENJI attacked, a huge flock of waterbirds suddenly took to the air with their wings beating loudly against the surface of the water. This noise caused the HEIKE to think that the GENJI had started their attack, and they fled in despair thus losing the battle. 22.-24. in the pass of Kurikara…In the battle in the Kurikara pass in 1183, the GENJI fixed torches onto the horns of bulls (the Genpei seisuiki is the sole source for this) and sent the herd towards their enemies. The HEIKE warriors were so frightened that hundreds of them jumped to their deaths in the deep ravines of the mountains near the pass of Kurikara. General Kiso Yoshinaka is said to have devised this strategy. 26. Ōsaka…This pass denotes the division between present-day Shiga prefecture and Kyoto City. 36. Tadanori, the lord of Satsuma… no Tadanori (1144-1184) was the younger half-brother (their mothers were different) of the Supreme HEIKE Leader Kiyomori. He had fought against the GENJI in the battles of Fuji River and at Kurikara Pass. He died in the battle of Ichinotani (near Kobe) in 1184. His title “lord of Satsuma” was mostly rhetorical. 41. FUJIWARA Shunzei…This nobleman was a renowned poet of his time and Tadanori’s poetry teacher. He was commissioned to compile and edit an imperial anthology of waka poetry. 42. Gojō Avenue…FUJIWARA Shunzei’s residence was close to the crossing of Gojō Avenue and Kyōgoku. 45. poetry anthology…this compilation of waka poems was finally entitled the Senzai wakashū. To have a poem included in one of the imperial anthologies was extremely prestigious as it ensured enduring fame and admiration for the poet. 60. setting off to the West…The HEIKE moved westwards from the capital Kyoto. After the battle of Ichi no Tani (close to Kobe, in Suma Bay), they chose ships for their flight, which ended at Dannoura, in the strait of Shimonoseki at the southern tip of Honshu.

Music Notes

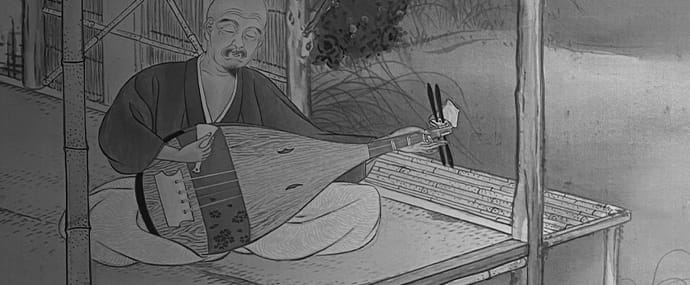

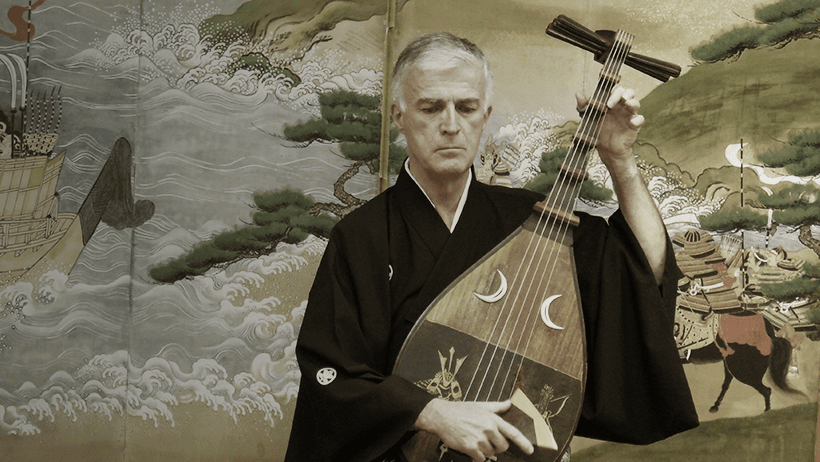

When composing Miyako ochi, YAMAZAKI Kyokusui conceived this ballad as a lyric work. The first four lines, the well-known opening of the Tale of the Heike, Gion shōja no kane no koe, embody the essence of the entire tale. It is astonishing that the musical setting of these four lines in the ballad — at least according to the notation is very close to the settings of many ballad openings. Only when listening to the performance of an experienced singer can the connoisseur recognize unusual details in the melodic treatment, which have been transmitted orally by the composer.

Only in the first quarter of the ballad (lines 10 through 18) do we find three energetic ‘attack patterns’ (seme) for the biwa commonly associated with battle narrative. These vocal/instrumental passages are necessary as the text describes the aggressive GENJI troops forcing the HEIKE clan to leave Kyoto for good.

The remainder of the work, some 75 per cent, however, is entirely lyrical. In this short ballad of 73 lines, there are five nagashi patterns, arioso sections that are the height of chikuzen biwa art. Not all of them span the standard length of three lines, but all accentuate sheer vocal beauty.

Lines 61/62, are a passage of rōei (singing of a Chinese poem), and lines 65/66 the setting for Tadanori’s waka included in the imperial anthology make use of a most elaborate melody. These two lines must be carefully interpreted as they are the vocal highlight of this ballad.