Meiji Period-search

saigo takamori

西郷隆盛

Introduction

SAIGŌ Takamori (1828-1877) was one of the most influential personalities of the late Edo and early Meiji periods, and dubbed “The Last True Samurai”.

SAIGŌ was born in Satsuma domain, present-day Kagoshima Prefecture, and served as a low ranking samurai official in his early career. He was recruited to travel to Edo in 1854 to assist the Satsuma daimyō, SHIMAZU Nariakira, in his efforts of forging closer ties between the TOKUGAWA shogunate and the Imperial court. Although SAIGŌ faced numerous political troubles with his outspoken convictions—he was arrested, then pardoned, then again banished etc—he eventually became influential in the early Meiji years. In 1871, for example, he was given charge of the government during the absence of the IWAKURA Mission to Europe (1871–72).

Saigō, who had initially disagreed with the modernization of Japan and the opening of commerce with the West, was famous for insisting that the Meiji government should spend money on military modernization. He was convinced that Japan should go to war with Korea in the seikanron debate of 1873 due to Korea’s refusal to recognize the legitimacy of the Emperor Meiji as head of state of the Empire of Japan. Other Japanese leaders, however, strongly opposed his plans, which finally led to SAIGŌ’s resigning from all his government positions and returning to his hometown of Kagoshima.

Shortly thereafter, a private military academy was established in Kagoshima for the faithful samurai who had also resigned their posts in order to follow SAIGŌ from Tokyo. These disaffected samurai came to dominate the Kagoshima government. Fearing a rebellion, the government in Tokyo sent warships to Kagoshima to remove weapons from the Kagoshima arsenal, which, however, provoked an open conflict. Although greatly dismayed by the revolt, SAIGŌ was reluctantly persuaded to lead the rebels against the central government.

The rebellion was suppressed in a few months by the central government’s army, a huge mixed force of 300,000 samurai officers and conscript soldiers. The Satsuma rebels numbered around 40,000, dwindling to 322 at the final stand at the Battle of Shiroyama, located within the present city of Kagoshima. During this battle, SAIGŌ was badly injured in the stomach. The exact manner of his death, however, is unknown. The accounts of his subordinates claim that he requested BEPPU Shinsuke to assist him in taking his life. Some scholars have suggested that neither is the case, and that SAIGŌ may have gone into shock following his wound, losing his ability to speak. Several comrades upon seeing him in this state would have severed his head, assisting him in the warrior’s suicide they knew he would have desired. Later, they would have said that he committed seppuku in order to preserve his status as a “True Samurai”.

SAIGŌ’s death brought the Satsuma Rebellion to an end. Although considered a rebel, the Meiji Era government, not being able to overcome the affection that the people had for this paragon of traditional samurai virtues, pardoned him posthumously in 1889.

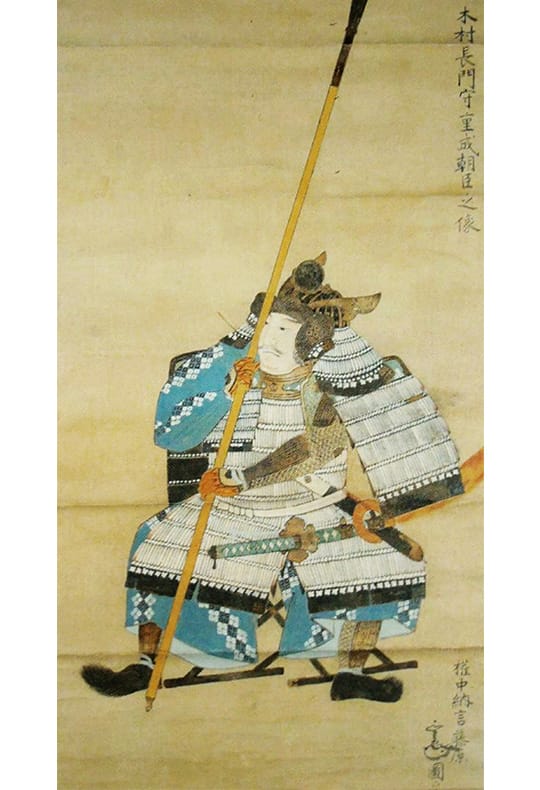

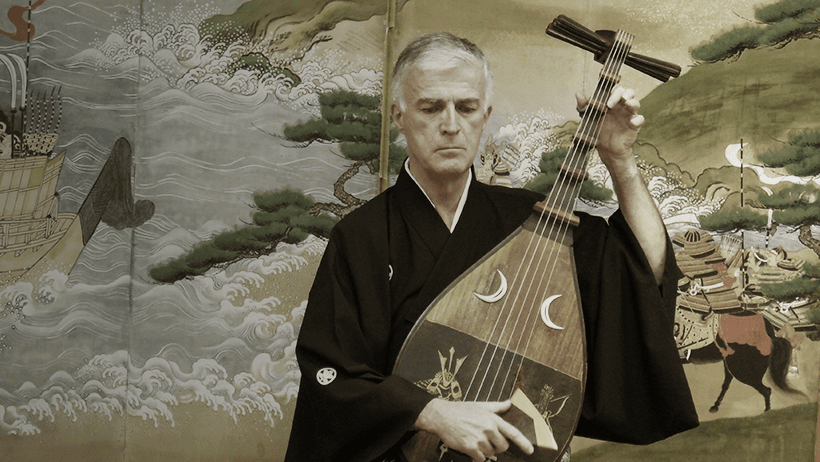

All Japanese know the bronze statue, created by TAKAMURA Kōun in 1898, at the south entrance of Ueno Park in Tokyo, which shows SAIGŌ walking his dog. In Kagoshima, SAIGŌ Takamori is practically a saint. The ballad Shiroyama retells the last battle, and is assuredly the most famous piece in the satsuma biwa repertoire.

Synopsis

The ballad starts after a brief survey of the military struggles, which end on Mt. Shiroyama in Kagoshima. SAIGŌ Takamori and his few remaining young samurai are attacked by six brigades of the Imperial Army. The fighting is fierce, but the government troops steadily advance. SAIGŌ observes the battle from a secure cave and is saddened to see his men with no chance to win. A sung poem (kanshi) expresses SAIGŌ’s equanimity by comparing him an untroubled hermit playing gō, a type of chess, in the face of death.

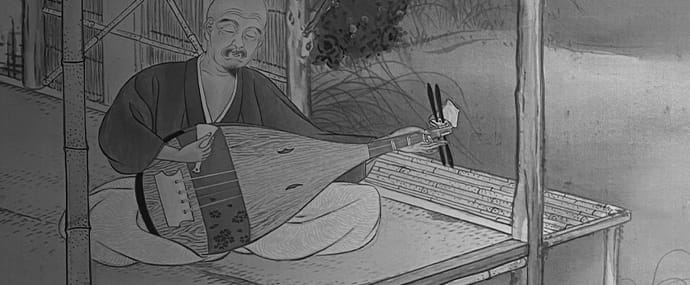

Night falls and the gunshots subside. For the small group on Mt. Shiroyama, it is time to drink the final cups of sake, and SAIGŌ offers the toast. A refined and talented samurai starts to play the satsuma biwa ballad, Young Atsumori. This late 12th-century story preserved in The Tale of the HEIKE, suits the young warriors who face a death that resembles Atsumori’s (see the ballad Kumagai to Atsumori). Everybody in the shelter take a brief respite only to soon hear once again war cries mingled with the roosters’ greeting to the rising sun. Intense fighting starts anew. The famous commander KIRINO encourages his men to give everything they have. Gun smoke engulfs the mountains and dead bodies are scattered everywhere. SAIGŌ seeing this reflects on his dreams of having such fierce young samurai — friends as well as foes, but all Japanese — fighting for the Emperor abroad. He then moves to the small valley of Iwasaki. The government troops, however, draw extremely near. A trumpet signal is heard, and SAIGŌ is shot in the stomach. Blood spills everywhere, but SAIGŌ has still enough power to prostrate himself and to show his reverence to the emperor. He prays for the emperor’s lengthy reign, and the expansion of the empire to lands beyond the islands of Japan.

After his prayer, SAIGŌ asks his close follower, BEPPU Shinsuke, to assist him in taking his life by cutting off his head. The young samurai, his hands trembling and overwhelmed by tears, feels unable to swing the sword. But when the enemies approach, he cries, “Forgive me!”, and cuts off the head of his revered master as requested.

After SAIGŌ’s death, another beautiful Chinese style poem (kanshi) about the tragedy of the “Last True Samurai” on Mt. Shiroyama is performed. The ballad ends with a prayer that the emperor may be eternally protected by the soul of SAIGŌ Takamori.

Lyrics

-

1. Heroic deeds span the oceans Heldentaten überspannen Meere,

Yūto shikai o ooitsutsu 雄図四海を蓋ひつゝ

-

2. and strength moves mountains, Willenskraft versetzt Gebirge,

chikara wa yama o nuku totemo 力は山を抜くとても

-

3. but the thousand-fold bonds of fate aber Schicksalsbande

chiji ni matsuwaru unmei no 千々に纏はる運命の

-

4. cannot be severed by swords. kann man nicht mit einem Schwert durchtrennen.

kizuna kiru beki tachi wa naku 絆切るべき太刀はなく

-

5. How tragic a hero to sacrifice himself Schmerzlich, dass ein Held sich selbstlos

eiyū aware sanzen no 英雄あはれ三千の

-

6. for three thousand young followers! für dreitausend Junge opfert.

shitei ni mi o ba makasekeri 子弟に身をば任せけり

-

7. But listen: SAIGŌ Takamori Doch nun hört: SAIGŌ Takamori

satemo SAIGŌ Takamori wa さても西郷隆盛は

-

8. attempted to dispel the disloyal cowards focht die Gegner der Korea-Frage an

seikanron o habamitsuru 征韓論を阻みつる

-

9. who hindered his hopes of seizing Korea. und wollte es den Unloyalen zeigen.

kanshinbara o harawan to 奸臣原を払はんと

-

10. He led 10.000 troops Fast zehntausend Reiter führt’ er an;

ichiman’yoki o insotsushi 一万余騎を引率し

-

11. and in vigorous high spirits von hohem Mut beflügelt

iki shōten no ikioi nite 意気衝天の勢ひにて

-

12. they emerged from Kagoshima. zogen sie von Kagoshima los.

Kagoshima utte idekeru ga 鹿児島打って出でけるが

-

13. The battles had continued several months Nach vielen Monaten des Kämpfens

tatakai sudeni sūgetsu ni 戦ひすでに数月に

-

14. and many of his supporters had been destroyed; hatten viele junge Krieger in den Schlachten ihren Tod gefunden;

watarite mikata uchiyabure 亘りて味方打敗れ

-

15. with a mere three hundred horsemen remaining, nur dreihundert Reiter blieben übrig.

wazukani nokoru sanbyakki 僅かに残る三百騎

-

16. to Mt. Shiroyama where the chill winds of autumn blew, In der Heimat braust’ der kalte Herbstwind auf dem Hügel Shiroyama,

shūfū samuki Shiroyama ni 秋風寒むき城山に

-

17. they returned to barricade themselves. wo sie Schutz und Zuflucht suchten.

kaeri kitarite tatekomoru 帰り来りて立て籠る

-

18. At this time, six loyalist brigades Doch da rückten Kaiserliche vor in sechs Brigaden,

kono toki kangun roku ryodan 此時官軍六旅団

-

19. gathered like clouds and mist schnell und unbemerkt wie Wolkennebel

unka no gotoku yosekitsutsu 雲霞の如く寄せ来つゝ

-

20. positioning themselves ten and twenty ranks deep, griffen sie mit zehn, ja zwanzig Schützenreihen an.

toe hatae ni torikakomi 十重廿重に取囲み

-

21. to crush the insurgent forces. Um jetzt vollkommen die Rebellen zu besiegen,

gyakuzokubara o uchitoreto 逆賊原を打取れと

-

22. The rebel forces, set upon with a furious intensity, attackierten sie mit ungehemmter Wucht.

ikioi hageshiku semekakaru 勢ひ劇しく攻めかゝる

-

23. nonetheless responded to this attack without faltering; SAIGŌ’s Krieger leisteten jedoch bewundernswerten Widerstand.

mikata wa hirumazu ōsenshi 味方はひるまず応戦し

-

24. both heaven and earth trembled Die Erde zitterte, der Himmel dröhnte

otakebi no koe toki no koe 雄叫の声喊の声

-

25. to the sound of their brave shouts and battle cries. ob dem Schlachtgeschrei.

tenchi o kuzusu bakari nari 天地を崩す計りなり

-

26. SAIGŌ, who watched from not far away Aus einiger Entfernung

sashimo hageshiki tatakai o さしも劇しき戦ひを

-

27. the ferocious fighting, schaute SAIGŌ den Gefechten ruhig zu,

yoso ni minashite Takamori wa 余所に見なして隆盛は

-

28. was calm in a distant cave. verschanzt in einer Höhle.

iwaya no uchi ni yūzen to 岩窟の中に悠然と

-

29. The formations of “crane wings and fish fins”, „Kranich-Flügel, Fisches-Flossen“ – solche Strategien dachte er sich

kakuyoku gyorin to jindatete 鶴翼魚鱗と陣立てゝ

-

30. positioned on the chess-board like stars in the sky, auf dem gō-Brett aus, wo viele Steine schimmerten wie Sterne.

uchitsu utaretsu hoshi no kazu 打ちつ打たれつ星の数

-

31. he gently swept away, Doch auf einmal wischte er sie sanft vom Spielbrett,

midaruru goishi sarasara to 乱るゝ碁石さらさらと

-

32. and the stones fell like dew from chrysanthemums. dass sie wie der Tau von Chrysanthemen auf die Erde fielen.

kobosuya kiku no tsuyu naran 零すや菊の露ならん

-

33. He then spread a sheet of paper to brush a poem: Danach zog er ein Papier hervor und dichtete:

yagate isshi o oshinobete やがて一紙を押のべて

-

34. In six months, a hundred battles and none won, In einem halben Jahr – noch keine Schlacht gewonnen

hyakusen kō nashi hansai no kan 百戦功無シ半歳ノ間

-

35. having fortunately returned to this hill in the hometown In der Heimat glücklich – auf dem Hügel meiner Stadt

shukyū saiwai ni kazan ni kaeru koto o u 首邱幸ニ家山ニ返ルコトヲ得

-

36. facing death calmly like an untroubled hermit, Im Walde sorglos lachend – bin ich ganz dem Tod gesonnen

warau ware shi ni mukatte senkaku no gotoshi 笑ウ儂死ニ向ッテ仙客ノ如シ

-

37. spending my last day quietly playing chess. In den letzten Tagen müßig – findet nur mein gō-Spiel statt.

jinjitsu dōchū kikyō kan nari 尽日洞中棋響閑ナリ

-

38. The night had already deepened, Als nun die Nacht hereinbricht und es immer dunkler wird,

sude ni sono yo mo fuke yukeba 既に其夜も更けゆけば

-

39. and the dramatic sound of gunfire verstummt die wilde Schießerei,

hageshikarikeru tsutsu no oto 劇しかりける砲の音

-

40. had at some point ceased, and in the heavens, bis endlich Ruhe einkehrt.

itsushika yamite ama no to ni いつしか止みて天の戸に

-

41. the wild geese cried as they crossed the skies, Gänse ziehen rufend in die Himmelsweite,

tokoyo no kari no nakiwataru 常世の雁の鳴き渡る

-

42. their voices faintly heard. ihre Stimmen werden in der Ferne immer leiser,

koe mo kasuka ni kikoetsutsu 声も幽かに聞えつゝ

-

43. It was now time for the final festive banquet, und so ist es Zeit,

kono yo no wakare to kumu sake no 此の世の別れと酌む酒の

-

44. in which drink was poured to bid this world farewell. das letzte Fest zu feiern.

utage takenawa to narinikeri 宴酣となりにけり

-

45. At this point, some admirable person, Da nun wendet sich ein junger Kämpfer

satemo yukashiya tarebito ka さても床しや誰人か

-

46. turned to the clear moon that would only shine this night, gegen Mitternacht

koyoi kagiri to sumiwataru 今宵限りと澄み渡る

-

47. and began to play with great skill. dem Vollmond zu

tsuki ni mukaite kakinarasu 月に向ひて搔き鳴らす

-

48. the biwa, and when this was heard: und schlägt sein biwa herrlich.

tenare no biwa no koe kikeba 手馴の琵琶の声きけば

-

49. “The blossoming cherries of Suma Bay, Junger Kirschbaum in der Bucht von Suma;

Suma no wakaki no sakurabana 須磨の若木の桜花

-

50. lose their petals to the storm, as young Atsumori fell, wo ein Sturm die Blüten von den Zweigen riss – ach junger Atsumori.

arashi ni chirishi Koatsumori 嵐に散りし小敦盛

-

51. and we, the red maple leaves, Hier sind wir nun Ahornblätter,

tagai no mi sae momijiba no 互の身さへ紅葉の

-

52. our lives brief as we await the storm.” die den letzten Sturm erwarten.“

arashi matsu ma no inochi nari 嵐待つ間の命なり

-

53. With rifles for pillows, the warriors Ihr Gewehr als Kissen auf dem Lager lässt die Krieger

tsutsu o makura ni tsuwamono ga 銃を枕に兵士が

-

54. Merely dozed, their dreams binding the brief pause nur in Halbschlaf sinken. Träumend hören sie

karine no yume o musubu ma mo 仮寝の夢を結ぶ間も

-

55. Until the cock’s cry at the mountain’s foot, am Fuß des Berges einen Hahn

naku ya fumoto no kudakake wa なくや麓の鶏は

-

56. announced the scarlet skies of the east. das Morgenrot im Osten grüßen.

tōtenkō to tsugewatari 東天紅と告げ渡り

-

57. The lingering moon of dawn shone through the clouds Durch die Wolken scheint der Mond,

kumoma o moruru zangetsu no 雲間を漏るゝ残月の

-

58. to throw its pale light on the white flags swaying like pampas grass. ein bleiches Licht auf Flaggen werfend, die wie Pampasgräser leuchten.

kage shirami yuku hata susuki 影白み行く旗薄

-

59. Again, the cries begin, Wieder hört man Schlachtenrufe

mata mo agareru toki no koe 亦も揚がれる喊の声

-

60. echoing through the hills. in den Bergen dröhnen.

dotto yama ni zo hibikikeru どっと山にぞ響きける

-

61. All were resigned to what must be, Alle reißen sich zusammen,

kanete kakugo no koto nareba かねて覚悟の事なれば

-

62. and that nothing should be feared nichts erschreckt sie

mikata wa nanika osoru beki 味方は何か恐るべき

-

63. and all charged the advancing enemies. im direkten Feind-Kontakt.

yosekuru teki o mukaiuchi 寄せ来る敵を迎ひ撃ち

-

64. “Let’s beat the hungry boars from Bungo „Als gält‘ es hungrig wild gewordne Bungo-Eber zu bekämpfen,

ana kokochiyoya Bungo jishi あな心地よや豊後猪

-

65. and fight fiercely, wollen wir uns mutig schlagen mit den Feinden

uchitoru sama ni nitaru zo ya 打取る様に似たるぞや

-

66. for it is our last battle. bis zum letzten Atemzug.

ima o saigo to tatakaite 今を最後と戦ひて

-

67. As warriors from Satsuma Hayato, Die Krieger aus dem Lande Satsuma,

Satsuma hayato no buyū o ba 薩摩隼人の武勇をば

-

68. we shall remain in tales of valor!” sie kämpfen nur für Ruhm und Ehre!“

kataritsugaseyo monodomo to 語りつがせよ者共と

-

69. KIRINO shouts to encourage the men, KIRINO begeistert seine Jungen,

KIRINO wa shū o hagemashite 桐野は衆を励まして

-

70. and they rage like wild lions. und so rasen sie wie Löwen.

shishi funjin to aremawaru 獅子奮迅と荒れ廻る

-

71. And so, they take their first steps on the Mountain of Death: Blinder Einsatz aber führt sie alle “Auf den Berg des Todes“.

ima koso shide no yamabumi ya 今こそ死出の山踏みや

-

72. The bullets fly, Kugeln hageln dicht,

shigeku tobikuru dangan ni 繁く飛び来る弾丸に

-

73. and on all sides confusion reigns, und rechts und links herrscht Chaos.

migi ni hidari ni rōzeki to 右に左に狼藉と

-

74. with felled corpses Tote liegen weit verstreut, und über die gefallnen Körper

uchitaosaruru shikabane o 撃ち倒さるゝ屍を

-

75. over which they leapt as they battled. fegt der Kampf hinweg.

odori koetsutsu tatakaeba 躍り越えつゝ戦へば

-

76. Gun smoke swirled Vom Schießen breitet sich der Pulverdampf in Wolken aus –

shōen kumo to uzumakite 硝煙雲と渦巻きて

-

77. and obscured the mountains. sie hüllen rundum Berg und Hügel ein.

yamakage miezu narinikeri 山影見えずなりにけり

-

78. SAIGŌ watched with a faint smile on his lips: Doch SAIGŌ schaut dem Treiben zu und lächelt.

Takamori uchimite hoho zo emi 隆盛打見てほゝぞ笑み

-

79. “Both friend and foe, „Freund und Feind

teki mo mikata mo shikishima no 敵も味方も敷島の

-

80. the heroic sons of this land. sind Heldensöhne unseres Landes.

Yamato onoko no isamashisa 倭男児の勇ましさ

-

81. For the glory of the Emperor Für den Dienst an unsrem Reich sich opfernd

kimi no miizu o totsukuni ni 君の御稜威を外国に

-

82. could easily shine abroad.” könnten sie vereint uns draußen in der Welt viel Ehre bringen.“

kagayakasan wa ito yasushi 輝かさんはいと易し

-

83. With these sentiments in his gut Solch belastende Gedanken regen sich in seinem Innern,

ana kokochiyoya muragimo no あな心地よや村肝の

-

84. and a clear heart doch sein Herz bleibt ungetrübt und ruhig.

kokoro ni kakaru kumo mo nashi 心にかゝる雲もなし

-

85. he stood with his few remaining followers Mit nur wenigen Begleitern

iza morotomo to tachiagari いざ諸共と立上り

-

86. and headed to the valley of Iwasaki. macht er sich zum Tale Iwasaki auf.

Iwasakitani ni uchimukau 岩崎谷に打向ふ

-

87. With the sudden call of a trumpet, Da plötzlich, ein Trompetenstoß!

orishimo rappa no koe kyū ni 折しも喇叭の声急に

-

88. the Imperial Army drew near Die Kaisertruppen greifen in der Nähe an

kangun chikaku semari kite 官軍近く迫り来て

-

89. and rained bullets on their part. und schlagen drein, als prasselte der Regen.

shino tsuku gotoku uchiidasu 篠突く如く打出だす

-

90. One struck Takamori Eine Kugel trifft

ichidan tonde Takamori ga Takamori

-

91. thudding into his stomach. und reißt ihm ratsch den Bauch auf.

hara o dotto zo uchinukikeru 腹をドッとぞ打貫きける

-

92. His spilling blood stained the grasses crimson, Blut strömt, flutet in das Gras und färbt es rot.

chishio ni kusa o somenaseru 血汐に草を染めなせる

-

93. he fell to his knees to face Da fällt er auf die Knie, verbeugt sich neunmal

daichi ni zashite kokonoe no 大地に坐して九重の

-

94. the Capital in worship. vor dem Kaiser in der fernen Hauptstadt.

miyako no kata o fushiogami 都の方を伏し拝み

-

95. “The flow of time is inevitable, „Nichts wird nun den Lauf der Zeit noch ändern,

toki no ikioi zehi mo naku 時の勢ひ是非もなく

-

96. and I, who started this revolt, Takamori, der Rebellenführer

koto o agetsuru Takamori ga 事を挙げつる隆盛が

-

97. the depths of my heart, kann sein Herz

kokoro no soko o ookimi ni 心の底を大君に

-

98. I shall never be able to convey. Euch nicht mehr öffnen.

kikoe agubeki yoshi nakute きこえ上ぐべき由なくて

-

99. As your subject, I leave this world Als ein treuer Untertan verlass‘ ich diese Welt

shin wa kono yo o makaru nari 臣は此の世を退るなり

-

100. with prayers for your continued longevity. und flehe, dass Ihr immerfort erstrahlt

kimi yorozuyo mo mashimashite 君万世もましまして

-

101. May your splendor cross the distant seas im kaiserlichen Licht, das übers Meer hin

miizu wa tōku unabara no みゐづは遠く海原の

-

102. to shine in radiance,” glanzvoll leuchten möge.“

soto made terasase tamaeya to 外まで照させ給へやと

-

103. He prayed in his heart. Voller Inbrunst betet er und

kokoro no uchi ni nenjitsutsu 心の中に念じつゝ

-

104. Finally, he turned to one side, wendet sich danach zur Seite.

yagate katae o furimukite やがて傍を振り向きて

-

105. “BEPPU, it is time!” he commanded. „BEPPU, schlag jetzt zu!“ befiehlt er

BEPPU kire to zo meijikeru 別府切れとぞ命じける

-

106. BEPPU was a brave man Aber BEPPU Shinsuke, ein tapfrer Kerl,

sasuga ni BEPPU Shinsuke wa 流石に別府晋介は

-

107. who revered SAIGŌ as father and as master, der in dem Sterbenden den Vater und den Lehrer ehrt,

chichi to mo shi to mo aogitsuru 父とも師とも仰ぎつる

-

108. but the hand holding the blade vermag nicht, seinen Meister SAIGŌ zu enthaupten.

SAIGŌō ni atekanete 西郷翁にあてかねて

-

109. pressed to the Venerable Elder Zitternd hält er in der Hand das Schwert,

yaiba motsu te mo uchinaete 刃持つ手も打痿へて

-

110. caused him to writhe with torment die Trauer sticht ihm in die Eingeweide,

harawata o tatsu uki omoi 腸を断つ憂き思ひ

-

111. and his eyes briefly veiled with tears. Tränenstürze trüben seinen Blick.

shibashi namida ni kurekeru ga 暫時涙に暮れけるが

-

112. Yet the enemies came, closer and even closer Nun rückt der Feind ganz nah heran.

teki wa iyoiyo chikazukinu 敵はいよいよ近づきぬ

-

113. “Forgive me!” he said, and with one stroke „Verzeiht mir!“ sagt er,

yurusasetamae to ittō o ゆるさせ給へと一刀を

-

114. of his blade, the dew fell from und mit einem Schwertstreich fällt er ihn. Ach schmerzlich ist’s –

oroseba aware matsugae no おろせば哀れ松が枝の

-

115. the needles of the pitiful pine branch. wie wenn von Kiefernadeln Tau heruntertropft.

hazue no tsuyu to chirinikeri 葉末の露と散りにけり

-

116. My solitary struggle crushed, I return. Umzingelt von den Kaisertruppen – suchten wir uns Schutz

kogun funtō kakomi o yabutte kaeru 孤軍奮闘囲ヲ破ッテ還ル

-

117. Within the fortress walls a hundred miles long verschanzten uns in einer Festung – hundert Meilen lang.

ippyaku no ritei ruiheki no aida 一百ノ里程塁壁ノ間

-

118. our blades are already broken, our steeds felled, Gebrochen ist mein Schwert – gefallen ist mein Pferd –

waga ken wa sudeni ore waga uma wa taoru 我ガ剣ハ既ニ折レ我馬ハ斃ル

-

119. The autumn wind buries our bones on the hill of my home. Über den Gebeinen weht der Herbstwind auf dem Berg der Heimat.

shūfū hone o uzumu kokyō no yama 秋風骨ヲ埋ム故郷ノ山

-

120. Rarely, once in a thousand years, In viel tausend Jahren tritt nur selten

senzai mare ni yo ni ideshi 千載稀に世に出でし

-

121. The hero’s fate is unfortunate. solch ein Held hervor – vom Schicksal hart getroffen

eiyū jiun tsutanakute 英雄時運拙くて

-

122. His ephemeral end accomplished, war sein Ende traurig.

hakanaki saigo o togekeru mo はかなき最後を遂げけるも

-

123. his spirit will last forever Seine Seele aber möge bis in alle Ewigkeit

mitama wa chiyo ni yorozuyo ni みたまは千代に万代に

-

124. to defend the Emperor‘s Glory die Kaiserliche Heiligkeit beschützen,

kimi ga miizu o mamoruran 君が御稜威を守るらん

-

125. to defend the Emperor‘s Glory die Kaiserliche Heiligkeit beschützen.

kimi ga miizu o mamoruran 君が御稜威を守るらん

Notes

9. Seizing Korea… (see also introduction). When SAIGŌ was a member of the Meiji government, he proposed an invasion of Korea. His plan was to go first by himself and provoke the Korean Royal Court by offensive behavior and talk. Their reaction would then give the Japanese a cause to invade the country. His fellow members in the Japanese government were against this plan which angered SAIGŌ deeply. In protest, he left the government and returned to Kagoshima with many fellow samurai from Kyushu. After several incidents, SAIGŌ and his followers came to be considered rebels and were attacked by the Imperial Army. The Imperial Army’s final attack is the core of this ballad. 16. Mt.Shiroyama… this is a hill within the city of Kagoshima, present-day Shiroyamachō. 29. “Crane wings and fish fins”…These terms belong to the official military vocabulary of the time. “Crane wings” indicates a troop formation in which the attacking soldiers cover an ample space of the battle field. “Fish fins” is the opposite: soldiers proceed shoulder by shoulder. 49.-52. Bay of Suma, young Atsumori…The piece Ko Atsumori (Young Atsumori) is one of the best-known ballads in the satsuma biwa repertoire, and recounts the senseless death of Atsumori, a young HEIKE warrior, in the hands of the GENJI warrior, KUMAGAI Naozane, in the Bay of Suma in the early spring of 1184. In the satsuma biwa-ballad, the death of Atsumori is compared to the image of falling cherry blossoms. The final hours of the young warriors on Mt Shiroyama, took place in late autumn, and the comparison this time is thus to the falling of red maple leaves. 64. Hungry boars from Bungo…Bungo was a domain of southern Kyushu. Because this region is relatively far from Kagoshima, tradition holds that boars from Bungo appearing in Kagoshima must be hungry, and therefore especially aggressive. 69. KIRINO… KIRINO Toshiaki (1838-1877) was originally a samurai from the Satsuma domain. He was one of the famous Meiji-era “Three Killers,” heroic warriors that were perceived as superlative and invincible. KIRINO first opposed the shogunate and entered the Imperial Army, but later switched sides and joined SAIGŌ. He was a gifted military commander, but he, too, died on Mt. Shiroyama. 105. BEPPU… BEPPU Shinsuke (1847-1877) was a samurai from Satsuma. He was an officer close with SAIGŌ and is said to have helped him take his life

Music Notes

This extensive ballad is often performed in a truncated format, not only because of length, but the shorter version also seems to have a stronger impact than the original’s elaborate narration of numerous smaller episodes. The first great challenge in a performance of the entire piece is the short battle in lines 18-25, a passage which ends with a dramatic virtuoso interlude (Chō no roku). To reach a dynamic climax so early in the narrative flow is extremely difficult for the singer. Shortly after, lines 34 through 37, there is a four-line Chinese style poem (kanshi) sung in the standard melodious shigin style. This song is subuded and, from the viewpoint of drama, something of a dead moment. These two extremes render the establishment of the musical flow extremely difficult for the performer. A common solution is to omit lines 18 through 37.

The most noteworthy musical aspect of this ballad, however, is its unique performance culture. There is no other piece in which performers treat standardized vocal melodic patterns with such freedom. It would appear that every performer desires to show that they have an even deeper understanding of SAIGŌ Takamori’s destiny. The Tachibanakai-school usually takes pride in the very solid musical notation of every detail, which intends to impede individual interpretations of a composition. SAIGŌ Takamori, however, is the exception; even for YAMAZAKI Kyokusui. She invented many distinctive turns of clearly fixed melodic patterns. The most flamboyant vocal renditions of this ballad, however, are produced by performers from Kagoshima. Regrettably, they are utterly impervious to artisitic critique: nobody can suggest to them that their interpretations of SAIGŌ’s final hours are far too individualistic, much too personal. They won’t listen to any artistic critique…ever.