Kyoto-search

sumidagawa

隅田川

Introduction

The plot of Sumidagawa has very old roots and is even connected with the Tale of Ise (Ise monogatari) from the Early Heian period (10th century). In the ninth chapter, Azuma kudari, a man made a journey to the East and reached the Sumidagawa River in the Land of Musashi. When he arrived at the riverbank, he noticed birds flying about. When he asked a ferryman for the name of these birds, he was told they are called miyakodori, “Capital birds.” This then reminded him of his hometown, the capital Kyoto.

This is the background for the story of YOSHIDA Umewakamaru, which KANZE Motomasa (?-1432) dramatized in the Noh-play Sumidagawa. This story was popular in the Edo period, and adapted by the Bunraku and Kabuki theatres, and other genres, in which they were referred to as Sumidagawa-mono. In 1884, the kiyomoto dance piece, Sumidagawa, was composed making use of a highly regarded poetic text by JŌNO Saigiku (1832-1902).

The English composer, Benjamin BRITTEN, saw a performance of the Noh Sumidagawa in Japan, and in 1964, composed the opera, Curlew River, basing his plot on the Noh-play. He referred to it as a Parable for Church Performance, as he had changed the plot into a Christian story set in the Middle Ages in England. The narrative, however, remains very much the same as the Noh-play.

Synopsis

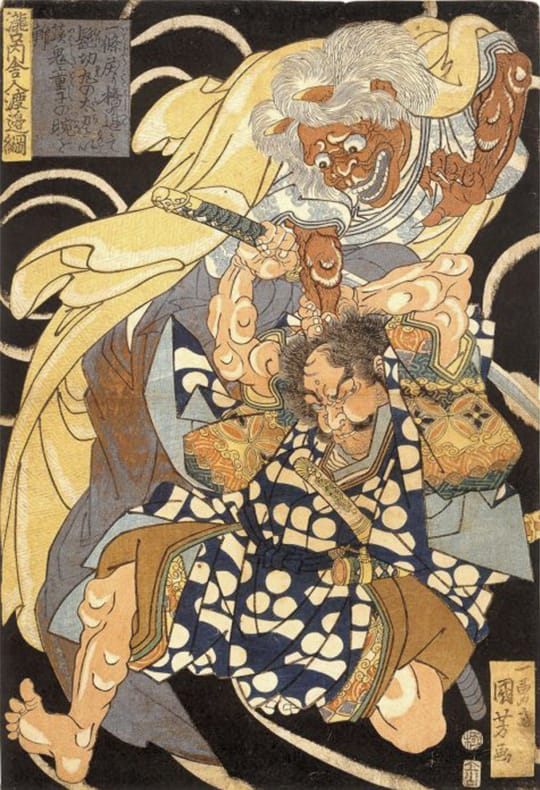

A widow’s only son, Umewakamaru, had been kidnapped by a slaver. Crazed over her loss she leaves her house in Kitashirakawa, Kyoto, and begins wandering eastwards. On her journey, she travels over Mt. Hiei, crosses Lake Biwa, asking children at every corner if they have seen her son, and begging strangers in the streets to bring him back.

Finally, she arrives at the riverbanks of Sumidagawa in the East. As she crosses the river on a ferryboat, she hears the chanting of a memorial service from the shore. She asks the ferryman for whom this service might be. He tells her the story of an ill boy who had been left alone at the bank by a slaver. The people of the village found the child and asked him about his background. He revealed his name, Umewakamaru, and told them the sad story of his abduction. The boy was aware of his imminent passing, and he uttered a last wish. There was a wind on the river Sumidagawa, and he felt that it must have come from Kyoto. He asked the people to plant a willow on his grave where its branches would sway delicately in the faintest breeze, and connect him to his home and his mother.

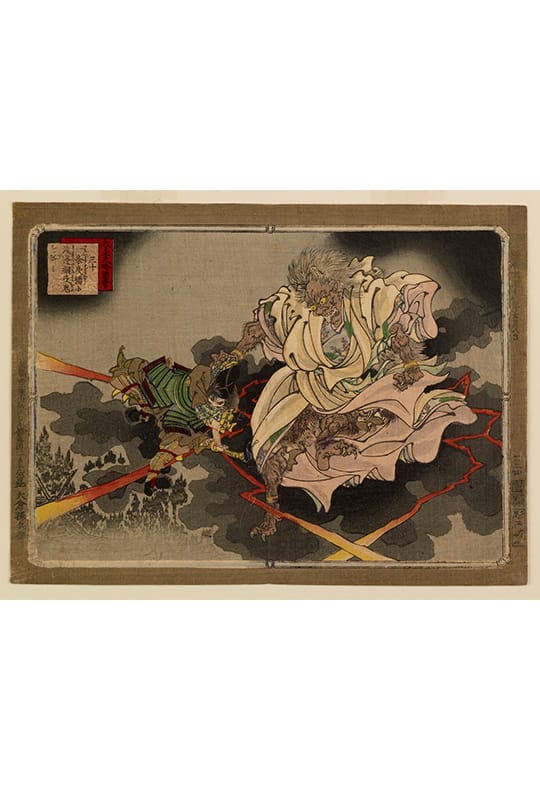

Listening to this story the woman realizes immediately that she has found her son – not alive but dead. She begs to be guided to the grave where the willow was planted. A priest and village people pray with her by chanting Namu Amidabutsu. As she chants, the mother hears her son praying, and finally, she has a vision of him. They reach out to each other, but the meeting is merely an illusion, and she is forced to accept the irrevocable loss of her beloved child.

Lyrics

-

1. Is the moon no more the same Ist der Mond nicht, wie er immer war

Tsuki ya aranu 月やあらぬ

-

2. and the spring no longer the spring of the past. und der Frühling wie der Frühling alter Tage.

haru ya mukashi no haru naranu 春や昔の春ならぬ

-

3. Man’s demise, however, resembles the banks of the Shirakawa River, Doch das Los des Menschen gleicht dem Shirakawa-Ufer,

mi no yukusue mo Shirakawa no 身の行末も白川の

-

4. where the mansion’s plum blossoms have been scattered wo ein Nachtsturm in dem Garten Pflaumenblüten

yakata no ume no yoarashi ni 館の梅の夜嵐に

-

5. by an evening storm. Far from her homeland, von den Bäumen riss. Die Heimatstadt verlassend

chirimidaretaru furusato o 散り乱れたる故郷を

-

6. the mother – with a darkened heart streift die Mutter wirren Sinnes

samayoi ideshi oyagokoro さまよひ出でし親心

-

7. wanders looking for her missing son. auf der Suche nach dem Sohn im Land umher.

ko yue no yami ni mayouran 子故の闇に迷ふらん

-

8. The mother of Umewakamaru Ja, Umewakamarus Mutter

sate Umewakamaru no haha goze wa さて梅若丸の母御前は

-

9. in search for her son fragte überall nach ihrem Kind,

waga ko no yukue tazune wabi 我が子の行方尋ねわび

-

10. is frenzied in her grief. verlor allmählich den Verstand.

kokoro mo itsuka kyōran to 心もいつか狂乱と

-

11. Her black hair Ihr schwarzes Haar

narase tamaite kurokami o ならせ給ひて黒髪を

-

12. was in disarray; and without footgear war aufgelöst, und barfuß

furimidashitsutsu kachihadashi 振り乱しつゝ徒跣

-

13. she moved on the eastward road. eilte sie verstört gen Osten.

Azumaji sashite zo kudaraseraru 東路さしてぞ下らせらる

-

14. Leaving the beautiful Capital, passing Mount Hiei, Sie verließ die schöne Hauptstadt und passierte den Berg Hiei,

hana no miyako o Ōhiei no 花の都を大比叡の

-

15. – its peak engulfed by white clouds – dessen Gipfel sich in weiße Wolken hüllte.

mine no shirakumo hedatetsutsu 峰の白雲隔てつゝ

-

16. making her way across Lake Biwa Viele Leute kamen ihr entgegen, während sie den Biwasee

yukikō hito ni Ōmiji mo 行きかふ人に近江路も

-

17. – on a (dangerously) floating boat – in einem steuerlosen Schiffe überquerte.

kojō no fune no kaji o tae 湖上の船の梶を絶え

-

18. longing for her child Heftig schmerzte sie die Sehnsucht nach dem Kind,

kogaruru ko ni wa Awazuno ya こがるゝ児には粟津野や

-

19. she cried like the cranes in the fields of Awazu and Unenono. sie heulte wie ein Reiher in den Feldern von Awazu und Unenono.

Unenono ni naku tazu no koe 畔の野に鳴く田鶴の声

-

20. “Children! „Ihr Kinder dort,

nōnō kore naru warabedomo なうなうこれなる童共

-

21. Have you seen my beloved young boy? wisst ihr denn, wo mein Junge ist?

koishiki waka o shirazaruka 恋しき若を知らざるか

-

22. And you people, crossing my way, Und hier, ihr Leute auf der Straße,

ika ni sore naru michiyukibito 如何にそれなる道行人

-

23. return my son!” gebt mir meinen Sohn zurück!“

waga ko kaesase tamae ya to 我が子返させ給へやと

-

24. And she grieved and wept in her travel robe. Sie war verzweifelt, und sie weinte bitter in ihr Reisekleid.

uramitsu nakitsu tabigoromo 恨みつ泣きつ旅衣

-

25. Finally, she reached the Sumidagawa River in Musashi Nun kam sie endlich in das Land Musashi an den Fluss Sumidagawa,

Musashi no hate no Sumidagawa 武蔵のはての隅田川

-

26. where she arrived at a ferry station. wo eine Fähre lag.

watari no hotori ni tsukitekeri 渡りのほとりにつきてけり

-

27. Water threading down their wings, Mit nassen Flügeln, Tropfen spritzend

nami no itosuji hikihaete 波の糸筋引はへて

-

28. frolicking seagulls joined their friends, tummelte sich eine Gruppe Möwen überm Fluss.

tomo uchitsurete asoberu wa 友打つれて遊べるは

-

29. “oh, aren’t they called ‘Capital birds’”, Heißen die nicht ‚Hauptstadt-Vögel’?

kore ya na ni ou miyakodori これや名におふ都鳥

-

30. On the other side of the river An dem andern Ufer, weißen Wolken ähnlich,

mukō kishibe ni shirakumo to 向ふ岸辺に白雲と

-

31. cherry blossoms – white as snow clouds – herrschte eine Kirschbaumpracht,

magō bakari no sakurabana まがふばかりの桜花

-

32. flowered in abundance. die weithin sinnbetörend strahlte.

sakimidaretaru awai yori 咲き乱れたるあはひより

-

33. From this place, the sound of a gong was heard. Von dort drüben hörte man das Schlagen eines Gongs.

shōko no oto no kikoyuru wa 鉦鼓の音の聞ゆるは

-

34. “For whom do they hold a mourning service?” „Für wen ist diese Totenmesse?“

ta ga naki ato no kuyō zo to 誰がなきあとの供養ぞと

-

35. she asked the ferryman. fragte sie den Fährmann.

watashimori ni koto toeba 渡守に言問へば

-

36. And with great elaboration, long like a spring day, Ruhig wie ein Frühlingstag,

haru no hi nagaki minarezao 春の日ながき水馴棹

-

37. he told her a story while slowly moving: gelassen stakend hub der Fährmann an mit folgender Geschichte:

sashimo isogade monogataru さしも急がで物語る

-

38. “Well, last year on the 15th of the 3rd Month, „Ja, es war vor einem Jahr, im dritten Monat am Fünfzehnten,

satemo kozo sangatsu jūgonichi さても去年三月十五日

-

39. a slave dealer brought a boy als ein Kindsentführer einen Jungen brachte

hito akiudo ga chigo hitori 人商人が稚子一人

-

40. to the banks of this river. und mit ihm den Fluss hier überquerte.

tsurete kono kawa watarishi ga つれて此の川渡りしが

-

41. Suddenly, the boy fell ill, Doch der Knabe wurde unversehens krank,

niwaka ni yamai sashi okori 俄かに病さしおこり

-

42. and was suffering terribly. er litt an fürchterlichen Schmerzen.

motte no hoka ni kurushimu o 以ての外に苦しむを

-

43. Leaving him behind at the banks over there Doch der Kindsentführer ließ den Jungen dort

ano kawagishi ni suteokite あの川岸にすておきて

-

44. the slaver ran away. am Ufer liegen, macht’ sich aus dem Staub.

akiudo soko yori nigesarinu 商人そこよりにげ去りぬ

-

45. Seeing this, the village people pitied the boy Die Leute aus dem Dorfe sahen dies und fühlten Mitleid,

sareba satobito awaremite されば里人あはれみて

-

46. and looked after him. und kümmerten sich um den Jungen.

samazama itawari sōraedo さまざまいたはり候へど

-

47. But his condition worsened. Dieser aber wurde schwach und schwächer.

tanda yowari ni yowariyuki たんだ弱りに弱りゆき

-

48. When his end was near Als sein Ende nahte,

inochi mo kagiri to mieshi toki 生命も限りと見えし時

-

49. he was asked about his origins. fragten sie ihn nach der Herkunft.

tokoro sujō o tazuneshi ni 所素性を尋ねしに

-

50. ‘I am from the Capital, from Kitashirakawa. ‚Von der Hauptstadt bin ich, von Kitashirakawa;

maro wa miyako no Kitashirakawa 麿は都の北白川

-

51. I am the only son of the officer YOSHIDA. bin das Einzelkind von Offizier YOSHIDA

YOSHIDA no shōshō ga hitorigo nite 吉田の少将が一人子にて

-

52. My name is Umewakamaru. und heiße Umewakamaru.

Umewakamaru to mōsu mono 梅若丸と申す者

-

53. My father died early and Mein Vater starb schon früh, ich lebte

chichi ni okure haha nomi ni 父におくれ母のみに

-

54. I lived together with my mother. mit der Mutter nur zu zweit.

soimairasete sōrō o 添ひまゐらせて候を

-

55. I was taken away by a slave dealer Von einem Kindsentführer wurde ich geraubt,

hito akiudo ni kadowasare 人商人にかどはされ

-

56. – that is why I am here now. und bin nun hier, verloren.

kayō ni nari hate sōrainu かように成り果て候ひぬ

-

57. When the wind blows from the Capital Wenn ein Wind weht von der Hauptstadt,

miyako no kata yori fuku kaze mo 都の方より吹く風も

-

58. I feel so homesick. hab‘ ich großes Heimweh.

ito natsukashū sōraeba いとなつかしう候へば

-

59. Could you therefore, after my death, Könntet ihr nicht hier am Weg

kono michinobe ni nakigara o 此の道のべに亡骸を

-

60. plant – on my grave – auf meinem Grab

uzumete ue ni hitomoto no 埋めて上に一本の

-

61. a willow for me?’ mir eine Weide pflanzen.’

yanagi o uete tamaware to 柳を植えて給はれと

-

62. His voice faltered Seine Stimme stockte,

koe taedae ni iinokoshi 声絶え絶えに云ひのこし

-

63. he took his last breath. und dann hauchte er sein Leben aus.

sonomama iki wa taenikeri そのまゝ息は絶えにけり

-

64. Today is the first memorial day of his death. Heute jährt sich nun sein Todestag,

kyō wa sono ko no meinichi nareba 今日は其の児の命日なれば

-

65. The village people performing the service die Leute feiern eine Messe,

satobitodomo ga kuyō no tame 里人共が供養の為

-

66. are chanting the Nenbutsu prayer.” singen das Nenbutsu Gebet.“

tonōru nebutsu to kiku yori mo 唱ふる念仏ときくよりも

-

67. “Oh ferryman, they are doing this surely „Oh Fährmann, alle tun das doch

nō watashimori sore koso wa なう渡守それこそは

-

68. for the child I am looking for!” für meinen Jungen!“

tazunuru waga ko ni arikere to 尋ぬる我子にありけれと

-

69. And before having finished with this outburst she fell down Kaum gesprochen stürzte sie

ii mo owarade funazoko ni 言ひも終らで船底に

-

70. to the floor of the ferry boat weeping bitterly. und wand sich weinend auf dem Fähren-Boden.

taore fushitezo naki tamō 倒れ伏してぞ泣き給ふ

-

71. The ferryman, hearing this, was shocked Als der Schiffer dies vernahm, erschrak er sehr

funabito kikite uchiodoroki 船人聞きて打驚き

-

72. and helpfully showed her und zeigte hilfreich ihr den Weg

itawari nagara Umewaka no いたはりながら梅若の

-

73. the way to Umewaka’s burial mound. zu Umewakamarus Grab.

tsuka no mae e to anai suru 塚の前へと案内する

-

74. “Ah – what grief! „Ach, wie greift mir das ans Herz!

aa ko wa satemo asamashiya 嗚呼こはさても浅ましや

-

75. I have one only wish in my life: Jetzt hab ich nur noch eine Bitte:

semete ichigo no nasake ni wa せめて一期の情けには

-

76. Please, dig up his burial mound, Schaufelt dieses Grab mir frei,

kono hakatsuchi o horikaeshi 此の墓土をほり返し

-

77. I want to meet him once more. damit ich ihn

arishi sugata o ima ichido ありし姿を今一度

-

78. Please, show him to me!” noch einmal seh!“

warawa ni misete tamaware to 妾に見せて給はれと

-

79. Desperately, she grasped the tombstone Verzweifelt stürzte sie zur Grabesplatte,

hishito sotoba ni toritsukite ひしと卒塔婆に取りつきて

-

80. crying helplessly beyond measure weinte außer sich vor Schmerz.

mi mo yo mo aranu kurui naki 身も世もあらぬ狂ひ泣き

-

81. until the sleeves of all around her were soaked with tears, too. Und allen, die da waren, wurden auch die Ärmel nass von Tränen.

yoso no sode o mo nurashikeri よその袖をも濡しけり

-

82. The villagers, nonetheless, asked the mother Doch die Leute von dem Dorfe

satobitodomo wa tonikaku to 里人共はとにかくと

-

83. as they proceeded with the memorial service, forderten sie auf, zu beten,

ekō o susume mairaseshi ni 回向をすゝめまゐらせしに

-

84. to strike the gong, even as she wept bitterly. und so schlug sie schluchzend ihren Gong.

haha wa nakunaku utsu shōko 母はなくなく打つ鉦鼓

-

85. Was it real or was it a dream that these sounds reached Ach, war es Wirklichkeit, war es ein Traum nur,

utsutsu ka yume ka jakkō no 現か夢か寂光の

-

86. the ethereal heavenly realms of The Pure Land. dass man aus der Tiefe, aus der Andern Welt, nun Klänge hörte.

jōdo no soko ni hibikuran 浄土の底に響くらん

-

87. Rising above all blossoming trees, the moon Über allen Blütenbäumen stieg der Mond herauf

hana yori noboru tsuki no kage 花より登る月の影

-

88. wrapped itself in the shadow of the Nenbutsu prayers und hüllte sich ins Nachtgebet des Nenbutsu,

oboro nagara mo yonebutsu no おぼろながらも夜念仏の

-

89. which echoed over the Sumidagawa River. das übern Fluss Sumidagawa hallte.

koe sumiwataru Sumidagawa 声澄み渡る隅田川

-

90. All the hearts turned to the west: Alle Herzen wandten sich gen Westen:

kokoro wa nishi e to hitosuji ni 心は西へと一筋に

-

91. “Hail, Western Paradise, „Heil dir, Paradies des Westens

namu ya saihō gokuraku sekai 南無や西方極楽世界

-

92. with all the thirty-six trillion Buddhas of the same name Trillionen Buddhas gleichen Namens

sanjūrokuman’oku dōmyō 三十六万億同名

-

93. and rank: Amidabutsu, gleichen Ranges.

dōgō Amidabutsu 同号阿弥陀仏

-

94. Praise to Amidabutsu Lob sei Amida Buddha.

Namu Amidabutsu 南無阿弥陀仏

-

95. Praise to Amidabutsu Lob sei Amida Buddha.

Namu Amidabutsu 南無阿弥陀仏

-

96. Praise to Amidabutsu Lob sei Amida Buddha.

Namu Amidabutsu 南無阿弥陀仏

-

97. Praise to Amidabutsu.” Lob sei Amida Buddha.“

Namu Amidabutsu 南無阿弥陀仏

-

98. Oh, how strange! Out from the grave Oh wie seltsam, in dem Grabe

ara fushigi ya na hakajirushi あら不思議やな墓標

-

99. a sudden move could be felt schien sich etwas zu bewegen;

niwaka ni ugokite dochū yori 俄かに動きて土中より

-

100. and a voice grew steadily louder: langsam hob sich eine Stimme:

shidai ni agaru koe sugoku 次第にあがる声すごく

-

101. “Praise to Amidabutsu.” „Lob sei Amida Buddha.“

Namu Amidabutsu 南無阿弥陀仏

-

102. Ah, now in midst of all the chanting „Hört ihr mitten in dem Chor,

nōnō ima no nebutsu no uchi なうなう今の念仏の中

-

103. one single voice was louder. wie eine Stimme lauter singt!

hitokoe takaku kikoeshi wa 一声高くきこえしは

-

104. “This must be my son’s voice, „Das ist die Stimme meines Sohnes!

masashiku waga ko no koe naruyo to まさしく我子の声なるよと

-

105. for sure this was no little cuckoo.” Nein, das war kein ,Trauerkuckuck‘, der da sang.“

shide no taosa no sore narade 死出の田長のそれならで

-

106. She wanted to hear his voice once more, Und da sie seine Stimme nochmals hören wollte,

ima hitokoe no kikitasa ni 今一声のきゝたさに

-

107. and when she chanted again “Namu Amidabutsu” sang sie wieder „Lob sei Amida Buddha“.

Namu Amidabutsu to tonōreba 南無阿弥陀仏と唱ふれば

-

108. a spring breeze came blowing Zu dieser Zeit begann ein abendlicher Frühlingswind zu wehen,

haru no yokaze wa fukeyukite 春の夜風はふけ行きて

-

109. that twirled the willow branches der die Weidenäste durcheinander wirbelte.

yanagi no kami mo uchimidare 柳の髪も打乱れ

-

110. Umewaka appeared Da, plötzlich wurde die Gestalt des jungen Umewakamaru

Umewakamaru no sono sugata 梅若丸の其の姿

-

111. as if he were real. wirklich, ja wahrhaftig.

utsutsu no gotoku arawaretari 現の如くあらはれたり

-

112. The mother was so happy Überglücklich war die Mutter,

haha wa amari no ureshisa ni 母は余りの嬉しさに

-

113. that she tried to embrace him. wollte ihren Sohn umarmen.

sugari tsukan to shitamaeba すがりつかんとし給へば

-

114. But he was no more than the reflection of the moon on the river; Aber unstet war er wie ein Spiegelbild des Monds im Fluss,

anaya itoyū mizu no tsuki あなや糸ゆふ水の月

-

115. her hands could not hold him – how sad. sie konnte ihn mit Händen nicht erreichen.

te ni mo tomarade kanashige ni 手にも止まらで悲しげに

-

116. “Mother!” cried his longing voice, Sehnsuchtsvoll klang seine Stimme: „Mutter!“

haha yo to shitō koe bakari 母よと慕ふ声ばかり

-

117. and here she called: “My dearest son!” Sie erwiderte: „Mein liebster Sohn!“

konata mo koishiki waga ko yo to こなたも恋しき我子よと

-

118. They called each other, mother and son. So riefen sie sich gegenseitig „Mutter“ – „Sohn“.

tagai ni yobō oya to ko o 互に呼ばう親と子を

-

119. Dense like The Five Obstacles, a mist of spring Ein Frühlingsnebel, den Fünf Hindernissen ähnlich,

utate ya goshō no harugasumi うたてや五障の春霞

-

120. separated them, what a pity. trennte beide – welch ein Leid.

tachi hedatsuru zo aware naru 立ち隔つるぞ哀れなる

-

121. The water flows, blossoms lose their petals and spring never ends. Das Wasser fließt, die Blüten fallen, doch der Frühling währet lang.

mizu nagare hana otsuredomo haru tokoshinae ni ari 水流レ花落ツレドモ春長ナエニ在リ

-

122. The wind is cold, the moon stands high, and cranes do not return. Der Wind ist kalt, der Mond steht hoch, die Reiher kehren nicht zurück.

kaze susamajiku tsuki takō shite tsuru kaerazu 風冷ジク月高ウシテ鶴帰ラズ

-

123. Then, in the morning dawn Nachdem das alles so geschehen, dämmerte der Morgen,

kakute shinonome honobono to 斯くて東雲ほのぼのと

-

124. when day arrived, und ein neuer Tag brach an.

akete kuyashiki tamakushige あけてくやしき玉櫛笥

-

125. Umewaka, who had not been seen a second time, Umewakamaru sah man nicht ein zweites Mal,

futatabi mienu Umewaka no ふたゝび見えぬ梅若の

-

126. disappeared again for eternity, er kam nie mehr zurück,

sugata wa chitose kaerikozu 姿は千歳かへり来ず

-

127. leaving behind a willow as a reminder. Erinnerung an ihn ist nur die Weide.

katami to nokoru aoyagi no かたみと残る青柳の

-

128. Like its thousand branches moving in the spring breeze So wie ihre tausend Äste sich im Frühlingswind bewegen,

chisuji no ito wa harukaze ni 千すぢの糸は春風に

-

129. we will be moved by grief forever rührt uns immerzu der Schmerz,

urami o nagaku hikunameri 恨を永くひくなめり

-

130. we will be moved by grief forever. rührt uns immerzu der Schmerz.

urami o nagaku hikunameri 恨を永くひくなめり

Notes

3. Shirakawa…is a river in the Eastern part of Kyoto. 8. Umewakamaru…during the Middle Ages, the suffix of maru in a name meant ”boy”, whereas ume refers to “plum” and waka to “young”. Therefore this name creates the image of “a young boy, bright like a blossom”. The poetic notion of “plum blossom” in line 4. is referencing this name. 19. Awazu and Unenono…these are both names of famous fields: Awazugahara is in the present city of Ōtsu close to Lake Biwa and Unenono is located in the city of Ōmi Hachiman. Without a context, the word awazu aurally understood as “not meeting,: but it is also a geographic name, and means “Millet Inlet”. It is used here to create a play of words in which the mother “does not meet her son”. 25. Sumidagawa…This huge river flows into Tokyo-Bay after passing through Musashi. 29. ‘Capital Birds’… in Japanese, these birds are known as miyakodori, which are “oystercatchers”. These birds are mentioned as they clearly connect the mother to her hometown Kyoto where her son had been abducted. 33. Gong… this gong, a shōko, is used in Buddhist ritual. Usually, it hangs in a wooden frame on a stand about 100 cm high, so that a priest can strike it while sitting. Here, the priest may be holding the gong in his left hand, and striking it with a mallet in his right hand. 51. Officer YOSHIDA… in the Noh-play Sumidagawa, on which this ballad is primarily based, the father is not referred to as “an officer”. The addition of rank is a later accretion seen in the Sumidagawa monogatari of 1656 and other sources. 66. Nenbutsu prayer…this prayer: “Namu Amida Butsu” (see also lines 93-97, 101 and 107) is the invocation of Amida Nyorai, a celestial Buddha with the ability to intervene in this world and save people. 105. Little cuckoo…is in Japanese shide no taosa which uses the characters for “death” (shi) and “leaving” (de), and thus serves therefore to from another wordplay. The more common name is hototogisu, the cry of which supposedly reminds people of immanent death. 119. The Five Obstacles…these are the five obstacles that prevent womn from attaining Buddhahood: a woman cannot become bonten, or Brahma; Emma, God of the underworld; Taishakuten, one of the Twelve Guardians of Heaven; a Tenrinō, the King of an ideal land; or a Buddha.

Music Notes

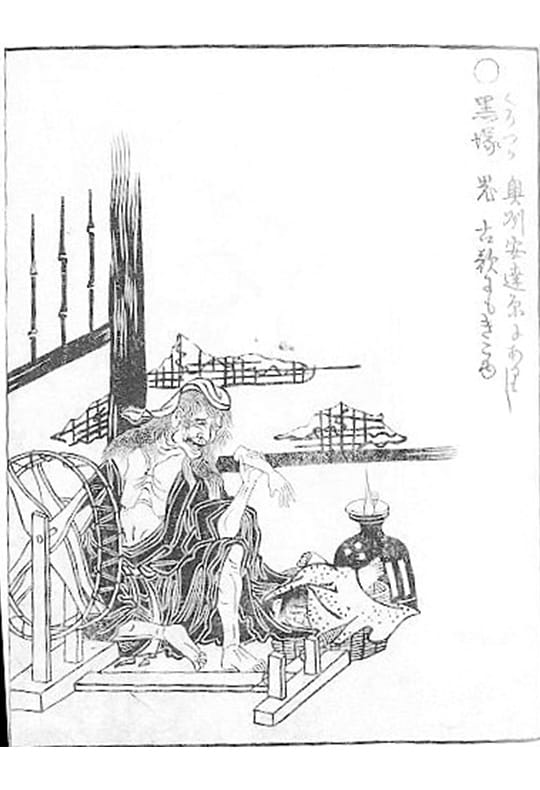

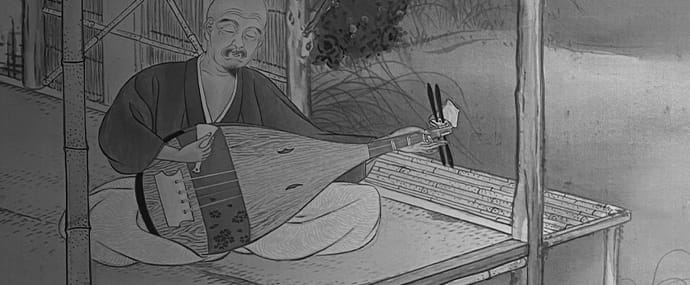

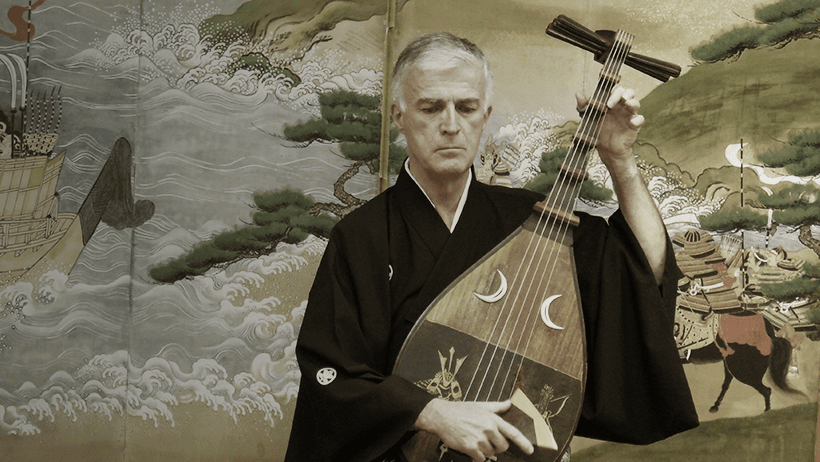

This 130-line ballad is one of the longer pieces in the chikuzen biwa repertoire, a full performance lasting over thirty minutes. For a variety of reasons, the piece is seldom performed. One problematic aspect of this sad tale is that the central figure is a mother. While there are many tragic tales in biwa narrative, most of the heroes are male. Since chikuzen biwa is mainly performed by women, the performer’s identification with a mother who has lost her son appears to be overly painful for most female performers. Nonetheless, there was one female performer from Hokkaido who focused on this ballad in the late 1980s to the extent she performed very little else. The reasons may have been personal and perhaps similar to the plot of this tragedy as pursuing one piece to the exclusion of others is highly unusual, and not seen with other chikuzen biwa ballads.

Another reason this work is seldom performed is the subdued atmosphere the performer has to maintain throughout the piece. There are no heroic passages in which virtuosity, either chant or nstrumental technique, can be displayed. Instead, the performer is challenged to preserve a constant musical expression of deep sorrow. The absence of virtuoso display, however, should not be taken to mean that the composition is without its challenges. A notable vocal challenge, for example, is the passage starting at line 91, in which the priest begins to pray, leading into four lines of a Namu Amida Butsu invocation, which requires imitating Buddhist chant.

This imitation of a religious service continues in the interlude after line 97, which was composed specifically for this scene. The biwa begins with a pattern of alternating “strong-weak-strong-weak” beats at a high pitch. These sounds mimic a Buddhist priest beating a metal gong as he chants. This instrumental imitation of a gong by the biwa may be shocking at the outset, but the interlude gradually shifts to a tender and delicate mood in which the supernatural encounter of the mother with her son is depicted. This transition requires extraordinary musical sensitivity.

The climax of the piece is assuredly the vision of the son in front of his mother. At this point, YAMAZAKI Kyokusui would – if only on stage – play the instrumental pattern Otsu no kuzure roku in an energetic, excited manner, in order to show the psychological struggle the mother experiences with the prospect of being reunited with her son. When teaching, however, YAMAZAKI asked the student to create a mystic effect by emphasizing the sonority of open-string strokes which characterize this interlude. The numerous alternating strokes of open strings a fifth apart remind the listener of the azusayumi. This so-called “bow” was used in shamanistic ritual, in which the string of the bow is beaten rhythmically over an extended period of time. Such a novel approach to the Otsu kuzure no roku, which is normally associated with battle scenes, is remarkably appropriate as this scene is unmistakably replete with shamanistic qualities.